Modems

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 12, 2022.

Want to go online? Chances are you'll be needing a modem—a device that lets your computer send signals back and forth along a telephone line. You need a different kind of modem to go online with a dialup connection, with broadband, or with (mobile broadband). What exactly are modems and how do they work? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: A modern broadband modem/router, which connects your computer to the Internet over a phone line.

Sponsored links

Contents

What is a modem?

Telephones are amazing: they can carry the sound of your voice from one side of the world to the other in a matter of seconds by making electricity flow down a wire. Telephones are also the power behind the Internet—without them, it would be almost impossible for most of us to go online.

The marriage of the telephone (a 19th-century technology) with the computer (a 20th-century innovation) was something of a shotgun wedding. Computer technology is largely digital: it involves storing, processing, and transmitting information in the form of numbers. But telephone technology is still partly analog: information is transmitted down phone lines as continuously varying electrical signals. How, then, do digital computers communicate across analog telephone lines designed to carry speech? Simple: they use modems, devices that turn digital information into analog sound signals for the telephone journey and then turn it back again at the other end. Think of modems as translators. Computers speak digital, and telephones speak analog, so you need modems to translate between the two.

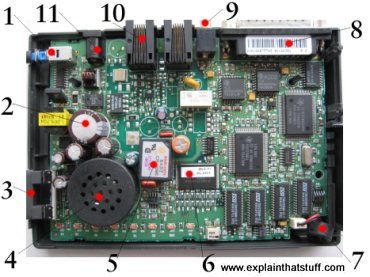

Photo: A typical US Robotics (3Com) dialup modem from the late 1990s. This one communicates via V.90 at 56k bits (binary digits) per second (kbps). I'll explain what that means in a moment. The little red LEDs along the front flicker on and off to tell you what the modem's doing.

What does a modem do?

Photo: A state-of-the-art HSDPA broadband wireless modem (sometimes called a "dongle") made by ZTE. You need one of these to surf the Net on a cellphone network.

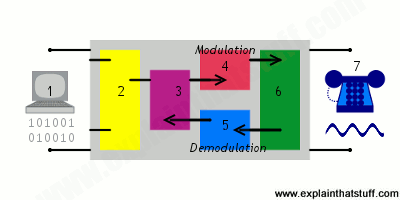

Suppose you want to connect your computer to an Internet Service Provider (ISP) using an ordinary phone line. The computer at your end needs a modem to modulate its digital signals (add them on top of an analog telephone signal) so they can travel down the phone line just like the sound of your voice. Once the signals have reached the other end, they have to pass through a second modem, which demodulates them (separates them out from the telephone signal and turns them back into digital form) so the ISP computer can understand them. When the ISP computer replies, it sends its signals through a modulator back down the line to you. Then a demodulator at your end turns the signals back into digital form that your computer can understand.

A box that we call a modem thus contains two different kinds of translators. There's a modulator (for transmitting digital signals out down the phone line in analog form) and a demodulator (for receiving analog signals from the phone line and turning them back into digital form)—and that's why it's called a modem.

Modulation is simply a fancy name for transmitting information by

changing the shape of a waveform. If you

send information by

making the peaks of a wave bigger or smaller, that's called amplitude

modulation or AM (because the amplitude is the size of the wave

peaks); if you send information by changing how often the peaks travel,

that's frequency modulation or FM (because

the frequency is the

number of peaks that travel per second). You may have heard the terms

AM and FM before, because they describe how radio signals travel. (You

can read a slightly longer explanation of modulation in our article on radio.)

Photo: Modems as they used to look. This contraption is called an acoustic coupler and its built-in modem allows you to connect your computer to a network using an ordinary landline telephone. Devices like this were popular when people had phones that were hard-wired into connection boxes and couldn't be unplugged or switched for modern-style RJ11 phone jacks. In some countries, it was illegal to connect directly to the phone network, so couplers like this acted as handy intermediaries. Unfortunately, you have to dial manually with equipment like this—and in the early days, usually with a rotary dial phone, so making a connection could be a very slow business, especially if you dialled a wrong number. Photo by courtesy of secretlondon123 published on Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons (BY-SA) licence.

Controlling modems

Think of how you use the telephone. You don't just pick up the receiver and start talking. You have to go through a series of quite orderly steps: you have to lift the receiver, wait for the dialing tone, dial each number so it's recognized, wait for the sound of the ringing at the other end, listen for the other person's voice, say hello, and then alternate your speech with theirs. If there's no answer, you have to know when to replace the receiver and hang up the call.

Handshaking

Modems have to behave exactly the same way, exchanging information in a very orderly conversation. If you've used a dialup modem, you'll have noticed that your modem opens the line, dials the number, waits for the other modem to reply, and "handshakes", before any real data can be sent or received. If there's no reply, it'll hang up the line and tell you there's a problem. Handshaking is the initial, formal part of the conversation where two modems agree the speed at which they will talk to one another.

Standards and speeds

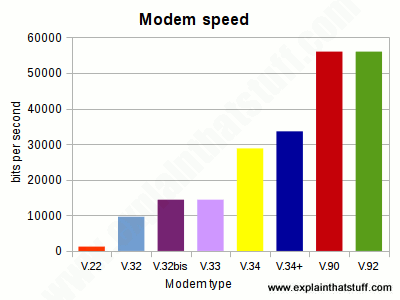

If you have a very fast modem but your ISP has only a slow one, the two devices will be forced to communicate at the slower speed. Every dialup modem works according to a particular international standard (a number prefaced by a capital letter V)—and this tells you how quickly it sends and receives data in bits (binary digits) per second (usually abbreviated bps). The most common standards are:

| Standard | Speed (bps) |

|---|---|

| V.22 | 1200 |

| V.32 | 9600 |

| V.32bis | 14,400 |

| V.33 | 14,400 |

| V.34 | 28,800 |

| V.34+ | 33,600 |

| V.90 | 56,000 |

| V.92 | 56,000 |

The older standards, such as V.22, assumed the connection between two computers was mostly analog; newer standards like V.90 achieve higher speeds by assuming the connection is at least partly digital.

Chart: Here's the same information from the table shown graphically. You can see that the most recent standards (like V.90) are about 4–5 times faster than the earlier ones.

Command sets

If you use the Windows operating system, you don't normally need to worry about how your modem communicates: it's all done automatically for you. But you can get your modem to send extra control commands, if you're having problems with it making calls. Using what's known as the AT command language (or the Hayes command set, for the company that invented it in 1977), you can change all kinds of other settings, including the maximum and minimum communication speed, how long the modem will wait before hanging up if the call is not answered, and so on. The exact commands you can use vary from manufacturer to manufacturer and from modem to modem, but a few are usually the same on every modem. For example, sending a command AT m0 almost always switches off the modem's loudspeaker so you don't get that irritating, electronic, handshaking chit-chat blasting out at you at the start of every session, while AT m1 keeps the speaker on until the connection is made (so you can check the handshaking sounds okay) and then disconnects it so you can enjoy some peace and quiet once you're online.

Different kinds of modem

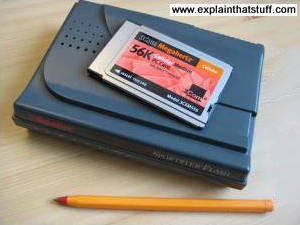

Photo: A pair of dialup modems. On the bottom, our typical 56K dialup modem. On top, there's a 56K credit-card-sized PCMCIA modem for use in a laptop. The laptop card modem has no loudspeaker, LED indicator lights, or other advanced features but, in other respects, works the same way. It takes its power from the laptop's PCMCIA connection and needs no external power supply.

Hardware modems

External modems—ones you connect to your computer through a cable or PCMCIA socket—are examples of what we call hardware modems: the modem functions are carried out entirely by chips and other electronic components in hardware.

Dialup modems are probably the most familiar hardware modems, though few us use them these days. A dialup connection to an ISP uses circuit switching, just like an ordinary phone call. But if you're using broadband to get a faster connection, you'll use your phone line in an entirely different way, using a data-handling technique called packet switching—and you'll need an entirely different kind of modem. (Read more about circuit and packet switching in our article about the Internet.) If you want to use broadband (packet switching) on a cellphone network, you'll need yet another kind of modem (known as an HSDPA modem).

If you link to the Internet without using a telephone line, either by using a wired ethernet connection or Wi-Fi (wireless ethernet), you won't need a modem at all: your computer sends and receives all its data to and from the network in digital form, so there's no need to switch back and forth between analog and digital with a modem.

Dialup modems have another handy feature: they can communicate with fax machines at high speed. That's why they're sometimes called fax modems. If you have fax software on your computer, you can use your modem to fax out word-processed documents and receive incoming faxes.

Photo: Detail of the indicator lights on a cable modem. Photo by courtesy of Wikipedia user Maduixa published on Wikimedia Commons in 2007 under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 licence.

Cable modems are designed to provide broadband Internet over cable TV connections rather than (as with other modems) the telephone network. Before fiber-optic broadband came along, cable was generally the fastest way of getting online. You need a cable modem in your home or office and there's a piece of kit at your service provider's premises that manages all the outgoing and incoming connections (a cable modem termination service or CMTS). The two are connected by coaxial cable or a combination of coaxial and fiber-optic cabling known as HFC (hybrid fiber coaxial). Cable modems are faster (provide higher bandwidth) than traditional (ADSL) broadband telephone modems and their speed doesn't degrade as you get further from the phone exchange (as traditional broadband connections do). However, many customers share the same bandwidth (so you can be affected by how many other local users are online) and they're less secure (since users don't have the same dedicated connection all the way to the premises), more susceptible to power outages (the telephone network is inherently more reliable), and tie you to a single provider (your cable company).

Software modems

As their name suggests, software modems carry out virtually all of a modem's jobs using software. That makes them low-cost, compact, and easy to upgrade, so they're a particularly popular choice in things like laptop and netbook computers where space is at a premium. Software modems rely on the host computer's processor to carry out some of their functions, which means they slow a computer down more than an external hardware modem with its own built-in processor and dedicated chips. At its most extreme, a software modem is just a DAA (data access arrangement): the most basic part of a modem that makes the physical interface between the relatively high voltage analog phone line and public phone network (on one side) and the lower voltage, digital modem circuits (on the other), ensuring the two can safely talk to one another.