History of communication

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: January 15, 2023.

Picture yourself a cave dweller, half a million years ago. Something exciting has happened—you've just discovered fire—and you want to share it with a friend in Australia or Canada. You whip out your phone to take a selfie but... oh, wait! Selfies haven't been invented. Nor have phones, friends overseas, or even places called "Canada" and "Australia."

It's hard to comprehend just how much the human world has changed since prehistoric times, when nothing bothered people more than finding food and shelter and staying warm. All kinds of inventions and discoveries have radically reshaped the planet we live on, but some of the most dramatic involve communications: recording information in different forms and sharing it with other people.

The coming of transportation technologies, such as railroads, cars, and jet engines, meant people could whistle round the world in days, hours, or even minutes. But communication technologies, like the telephone, radio, and fiber optics, shrunk the same world to a point a beam of light could cross in under a second. Even more radically, most forms of communication, from the alphabet to the Internet, let us share thoughts, ideas, and history itself in both space and time: with friends alive now and people far in the future who haven't even been born. How did ancient communications technology become the power behind modern civilization? Let's take a closer look!

Listen instead... or scroll to keep reading

Photo: Movies in a box: Thomas Edison's pioneering movie camera, pictured in his office and library at West Orange, New Jersey. Credit: Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Sponsored links

Contents

Writing and printing

Our memories, though amazing, are fragile and fallible. How, then, to record things like land transactions, trade, and taxes? That was how writing came to be invented, in ancient times, some 5,000–10,000 years ago, originally in the form of simple marks pressed in clay or notches carved into sticks and bones. [1]

Why stop there? The idea of using symbols to represent more things—spoken thoughts, stories, and increasingly complex ideas—was such a good one that it seems to have appeared independently, in different parts of the world, at slightly different times. As with many other inventions, there's no single point at which language was suddenly invented and no single language from which all others were derived. [2] One of the first written languages appeared c.3500BCE, developed by the Sumerians (in a region now in Iraq), who pressed sticks into clay to make symbols. This evolved into a more sophisticated form of writing called cuneiform, which was used to represent picture symbols (pictographs), syllables, and words in wedge-shaped grooves pressed into soft clay. Cuneiform (which means "wedge-shaped") is generally considered to be the first, proper form of human writing and it remained in use, in various forms, for about 3000 years. Although it looks like a strange written language, it's actually a "writing method" that was used with over a dozen different languages, in different places, at different times. [3] The ancient Egyptians followed on, a little later, with their famous system of hieroglyphs (incorporating pictures of everyday things like eyes and birds); and the Chinese too, invented a system of written pictographs, c.1250–1000BCE, essentially the ancestors of the thousands of hanzi characters that they use to this day.

Photo: Hieroglyphics in a temple in Karnak, Egypt. Photo by Maison Bonfils (Beirut, Lebanon) courtesy US Library of Congress.

A few hundred years later, c.1700BCE, the Semitic people in the Mediterranean had a brilliant idea: writing language down using an alphabet (a limited set of building blocks that can be rearranged to make every possible word). Different alphabets evolved around the world at different times: the Phoenician (c.1100BCE), Aramaic/Arabic (c.800BCE), and Hebrew (c.800–300BCE) alphabets developed later, and the Greek (c.800BCE), Etruscan (c.700BCE), and Russian Cyrillic (c.900CE) alphabets later still. The Roman (or Latin) alphabet evolved from the Etruscan, spawning the alphabet still used in much of the western world to this day. [4]

Writing materials

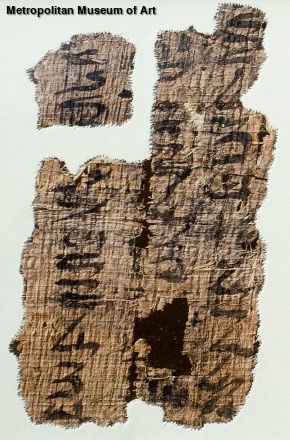

Photo: Papyrus fragment from ancient Egypt, c.2030–1640BCE. Photo courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Writing down and sharing thoughts meant not just inventing the idea of languages and alphabets but developing practical ways of recording words that would last longer than human memories. The Egyptians pioneered papyrus (the forerunner of paper, made from the fibrous pith of swamp plants) c.3000BCE. It was widely used by the Greeks and Romans, who also used parchment (and an especially fine version of it, called vellum), made from dried animal hides, which is also believed to date back to the ancient Egyptians. [5]

The Greeks and Romans wrote on papyrus scrolls (long rolls of paper or paperlike materials wrapped, like paper kitchen towels, round wooden holders). Later, people tried writing on slabs of wood covered in wax into which marks could be scratched with a stick and rubbed out if necessary. This idea was known as a codex and it gradually evolved into the paper books we have today, which began as parchment sheets (dried sheep and goat hides) crudely stitched together. Early Egyptian writers daubed their papyrus with some of the first inks, made from lampblack (a kind of soot) bound with gum arabic (a simple glue made from things like acacia trees) and water. Ostraca (essentially, bits of broken pottery) was another very common writing material in the ancient world.

It was the Chinese who made arguably the greatest leap in writing technology when they developed paper, from crushed tree bark, in 105CE (and, according to some sources, several centuries earlier). The Chinese had developed their own inks, possibly as early as 3000–4000BCE, also based on materials like lampblack and soot from burned pine trees, and something called "stone ink," which may have been based on graphite (soft carbon). [6]

Printing and copying

Photo: Type: The metal keys of an old typewriter make printed letters appear on paper in any order you choose. This idea dates back to ancient China.

Another great Chinese invention (c.600CE) was the idea of printing things by carving pictographs, in reverse, into blocks of wood, coating them with ink, and pressing them against paper. With woodblock printing, as this is known, you could make many copies of the same page and give it to lots of people at once. An even cleverer Chinese idea, which dates from around 700CE (and was first described by scientist Shen Kuo c.1100CE), was to carve individual pictographs into smaller wooden blocks ("type") that could be rearranged on the page to make different messages—an idea we'd now called "movable type." According to T.H. Tsien, writing in Joseph Needham's epic history of Chinese science and technology: "Of all the products from the ancient world, few can compare in significance with the Chinese inventions of paper and printing." [7]

Printing utterly transformed the world a few hundred years later when it was rediscovered by a German named Johannes Gutenberg (c.1400–1468) and incorporated into his famous invention: the printing press. This radical invention made it possible to produce books, such as the bible, in large quantities, so paving the way for mass education and literacy and the idea of preserving human knowledge in forms that could be passed from generation to generation. [8]

Photo: Printing presses changed the world. This one was used by Benjamin Franklin in the 1730s. Photo from Carol M. Highsmith's America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, courtesy US Library of Congress.

Today, most of us are printers, though we might use old-fashioned things like typewriters (developed from the 1860s onward by Christopher Latham-Sholes, 1819–1890); photocopiers (invented in the 1940s by Chester Carlson, 1906–1968, and pioneered by Xerox); inkjets (pioneered by the Japanese Canon company in the 1980s); laser printers (invented in the 1960s at Xerox by Gary Starkweather, 1938–2019); or publish our words on the World Wide Web (invented in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee, 1955–). Paper is just as important as ever, but we also read our words from things like LCD computer screens and the "electronic ink" displays of ebooks. All these inventions, though ground-breaking in their own way, are built on the earliest and most important human communication technologies: writing, alphabets, type, and printing.

Near and far

Writing things down as a permanent record was a great advance for humankind, but as transportation effectively made the world a smaller place, so the need grew for reliable long-distance forms of messaging. In fact, innovations in transportation and communication have constantly nudged one another forward: better transportation means your circle of trading partners, friends, and relatives are ever more widely dispersed—so you need even better communications technology to keep in touch with them. But the wider your contacts, the more you're likely to need better long-distance travel and transportation to meet and exchange goods with them.

Express and semaphore

Our idea of exactly what "long distance" means have changed radically.

Back in ancient times, it probably meant as far as you could hear someone's shouts or drumbeats, see their burning torches or smoke signals, or carry a message by hand or horse; there were few other ways of sending messages very far. Hand and horse still set the limit for how far information could travel in a certain time. In ancient Greece, "marathon" runners carried written messages many miles. (The name comes from the the legend of Pheidippides, a Greek who reputedly carried news of the Battle of Marathon some 42km or 26 miles to Athens, the Greek capital, before collapsing and dying on the spot, in 490BCE.)

Photo: Don't shoot the messenger! Pony Express riders carried messages long distances, on horseback, in the mid-19th century. Photo of a statue by sculptor Thomas Holland in Old Sacramento, California by Carol M. Highsmith. Credit: The Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The Persians, who were defeated at Marathon, preferred sending messages on horseback—an idea later reinvented in things like Wells Fargo, American Express, and the Pony Express, all of which carried messages (or sometimes money) by horse or stagecoach. [9] Communication glimpsed the future, toward the end of the 19th century, when a Frenchman named Claude Chappe invented a way of sending messages over long distances from tall towers. Semaphore ("sign carrying"), as it was known, used wooden, pivoting arms that could be moved up and down to represent different letters with a simple code.

All these things suffered the same basic drawbacks. First, even in things like semaphore, messages were essentially being sent mechanically—by clumsy, unnatural devices that were slow to operate. (Imagine wanting to ask someone out on a date and first having to light a large bonfire so you can send them smoke signals.) Second, where messages were physically carried, they could travel no faster than humans or animals could move them. Third, from messenger runners to Pony Express, most of these methods involved getting someone else to send a message on your behalf; you couldn't just do it yourself. This all changed in the 19th century when scientists and inventors learned to harness the power of electricity for practical purposes—so people could, gradually, send long-distance messages all by themselves.

Telegraph and telephone

The telegraph was a kind of "electrical upgrade" of the semaphore—a way of sending coded messages down a length of electric cable instead of as visual signals through the air. It was first proposed in Scotland in 1753 by someone writing in a magazine and signing themselves, anonymously, "C.M." Over the next 80 years, many inventors tried out experimental variations on this theme before the commercially viable Cooke and Wheatstone system was finally developed, in 1837, by British scientist and prolific inventor Sir Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875) and Sir William Cooke (1806–1879). Using six wires (for sending the signal), and five moving pointers (for displaying the message), it was relatively cumbersome. That was largely why it was succeeded by the simpler, more reliable, two-wire Morse telegraph introduced in 1844 by American Samuel Morse (1791–1872), featuring his famous Morse code, which uses dots and dashes (short and long pulses of electricity) to represent the letters of the alphabet. [10]

Artwork: Samuel Morse demonstrates the telegraph. Artwork from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1871, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Telegraphs transmitted at the speed of electricity—far faster than horses or even steam locomotives could carry messages—but they still suffered the other two drawbacks of classic, long-distance communication: they used clumsy "keys" to send letters and words in coded form, which meant messages could be sent and received only at special offices by trained telegraph operators. Fortunately, the 18th century inspired various inventors to experiment with converting the sound of their own voices into electrical signals that could be sent, in real-time, down electric cables—the basic principle of the telephone. Most of their names are largely forgotten today, including a German named Johann Philip Reis (1834–1874), French engineer Charles Bourseul (1829–1912), Italian Antonio Meucci (1808–1889), and American Elisha Gray (1835–1901). Rightly or wrongly, the name we remember as the telephone's inventor is that of Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922), who patented his version of the technology in 1876. The telegraph and telephone systems eventually evolved into ways of sending entire documents down a wire by telex (a "teleprinting" system developed in Germany in the 1930s) and fax (developed in its familiar, modern, electronic form in the 1960s).

Photo: Fiber optics sends messages in laser light beams. Photo by Greg Vojtko courtesy of US Navy and Wikimedia Commons.

Four years after his original patent, Bell developed what he considered "the greatest invention I have ever made; greater than the telephone." [11] Called the photophone, it was a way of sending telephone calls without any wires at all, coded inside super-fast beams of light. That made it a forerunner of fiber optics: a way of sending information (such as phone calls or Internet data) down hair-thin strands of glass or plastic at the speed of light. Though the science dates back to the mid-19th century, fiber optics really dates back to the mid-20th century: Heinrich Lamm and Walter Gerlach experimented with the idea for medical use in the 1930s; in the 1950s, Indian-born Narinder Kapany (1926–2021) and British physicist Harold Hopkins (1918–1994) sent the first pictures down fiber cables; and in the 1960s, Chinese-born US physicist Charles Kao (1933–2018) and George Hockham figured out how to send use the technology for sending messages over long distances. [12]

Sponsored links

The reach of radio

Bell's 1880 photophone was, arguably, the world's first mobile phone; it demonstrated the idea of making "wireless" phone calls, but it was too far ahead of its time and never caught on.

Mobile phones arguably trace back to a Canadian engineer named Reginald Fessenden (1866–1932), who used radio sets for communicating weather reports in Maryland, back in the early 1900s, spawning the commercial "Fessenden Wireless Telegraph System," and eventually making possible things like emergency service telephones (in the 1920s) and taxi phones (around the 1940s). Modern, mobile cellphones use electromagnetic radio waves for sending and receiving their calls, and a system of towers centered on overlapping, honeycomb-shaped zones called "cells"; this idea was invented in 1973 by Martin Cooper of Motorola. Between Alexander Graham Bell, in the 1870s, and Martin Cooper, in the 1970s, stretches the bold, brave history of wireless radio.

Wave hello

Radio began life in the mid-19th century as a scientific curiosity. In the 1860s, Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) had figured out the mysterious connection between electricity and magnetism—they were two sides of the same coin—and suggested that both traveled in wave form at the speed of light. Heinrich Hertz, a German physicist, confirmed this in his laboratory in 1888 when he sent the first electromagnetic wave. An English physicist, Sir Oliver Lodge (1851–1940), took things a few steps further, devising some of the basic apparatus for sending and receiving these "Hertzian waves" (as they were originally known) and sending the first radio message at a meeting in Oxford, England in 1894. Nikola Tesla (1856–1943), the great underrated genius of the electrical age, also made important steps forward in sending and receiving "wireless" signals—by radio.

Photo: Radios like this trace their history back to 1888, when Heinrich Hertz made the first electromagnetic wave in his laboratory.

But it was Italian Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937) who made radio a world-beating invention, with the same magical mix of scientific inspiration, entrepreneurial chutzpah, and marketing flair that people like Elon Musk demonstrate today. In December, 1901, in a particularly famous demonstration, Marconi sent a radio transmission from Cornwall, England to Newfoundland, Canada some 2200 miles (3500 km) away. It was such a long distance that many thought it impossible, but Marconi figured (correctly) that the radio waves would bounce off part of Earth's atmosphere (the ionosphere), just like light bounces off a mirror, in effect following Earth's curvature. The theory of how this worked was explained the following year by oddball British physicist Oliver Heaviside, (1850–1925). [13]

Thanks to electronics pioneers like Lee De Forest (1873–1961), who invented the triode amplifying vacuum tube in 1906, and John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley, who invented the transistor, in 1947, radio receivers soon became small enough to power with batteries and carry wherever you went. They were, very crudely speaking, one-way mobile phones!

Photo: Transistors like this made it possible to shrink pieces of communications equipment—such as radios, TVs, and phones—so they became small, lightweight, and portable.

From pictures to moving pictures

Freezing the world into still pictures has always been a fundamental part of how people communicate. Think of cave paintings, hieroglyphics, or Chinese pictograms. Think, indeed, of the whole history of human art. But painting takes time and skill. If you have neither of these things, but still want to catch an accurate picture of things you can see you need a camera—another invention that dates back to ancient China. The Chinese developed the ancestor of modern cameras, the camera obscura, and first wrote down details of how it worked around 500BCE, though it's believed to be a much older idea possibly even dating to prehistoric times. [14] In one classic early form, it was a darkened room with drapes drawn across the windows into which a tiny hole was bored. Light rays streamed through the hole, crossed over, and projected an upside-down image of the outside world onto the opposite wall.

Photographs

The Chinese clearly knew the optics of making images, but not how to record them permanently. That invention didn't appear for another two millennia, in the 18th century, when British chemists found that certain silver-based chemicals would change their nature when they were exposed to light. In 1827, Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) made the first black-and-white photo using the same science, later inspiring another Frenchman, Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), to take what were effectively the first popular photos, known as daguerreotypes. Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) discovered how to make better photos using a "negative" (reversed color) image that was then developed into a final "positive" print.

Photo: By the 1930s, cameras were convenient and portable. This is an English-made Soho Cadet with a case made from tough Bakelite plastic.

All these early photos took time to capture—Niépce's first photo took eight hours and daguerreotypes needed 10 minutes—but better methods were just around the corner. Another Englishman, Frederick Scott Archer (1813–1857), used glass "plates" coated in silver chemicals to take snapshots in seconds. And the final step, in the development of classic photography, happened in 1883 when an American inventor named George Eastman (1854–1932) discovered how to transform Archer's cumbersome plates into small, cheap, plastic strips called film. Eastman went on to invent easy-to-use, popular film cameras under the Kodak brand name; his rival, Edwin Land (1909–1991), went one step further by inventing Polaroid cameras that could take, develop, and print instant photos. Land's first public demonstration was an instant picture of his own face; in effect, he'd invented the selfie.

Movies

The human world is a restless place: nothing stays still for long. Taking photos was a wonderful technological advance, but it didn't solve the problem of how to record things that change before your eyes. Many inventors toyed with the difficulty of turning still images into moving ones in the 19th century. Indeed, the first attempts to do this were, quite literally, toys, such as the phenakistoscope (a disc covered with still pictures that leaped to life when you spun it around) and the zoetrope (which worked in a similar way, except the images were printed on the inside of a spinning cylinder and viewed through a slit).

Photo: Eadweard Muybridge's studies of moving animals (and people) paved the way to the movie age. Photo courtesy of US Library of Congress.

Following the invention of cameras, others tried to capture movement using a sequence of photos taken one after another. Most famously, in the 1870s, American Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) used rows of cameras to take successive shots of moving people and animals. A few years later, Frenchman Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904) developed a camera on a long pointed stick that took photos of fast-moving things in rapid succession. American William Dickson (1860–1937) saw what Muybridge and Marey had done and, working with his boss, Thomas Edison (1847–1931), developed what was effectively the first modern movie camera, the Kinetograph, in 1893. The films it took could be viewed by loading them into a rattling, viewing machine called a Kinetoscope, but only one person could see them at a time (usually after paying a few cents in a "peepshow" booth). The final piece of the puzzle—the invention of what we now call movies—happened in Paris, France in the 1890s when two brothers, Auguste Lumière (1862–1954) and Louis Lumière (1864–1948) invented a better movie-making system that projected its pictures onto a wall, big enough for many people to see at the same time; their first movie theater opened in 1895. The first movies were black and white, but color ones appeared about a decade later when Kinemacolor was invented in 1906 by George Albert Smith (1864–1959). [15]

Television

Photo: An early portable TV from about 1955.

Today, many of us view movies (and other programs) not in movie theaters but in our own living rooms. What made that possible was the invention of television, which was effectively a marriage of radio technology and movies. In theory, it was a relatively small step from radio to television—all you had to do was send pictures through the air as well as sounds.

In practice, that meant devising ways to "scan" moving pictures (turn them into "chunks" that could be transmitted), and it took the combined genius of several brilliant electrical pioneers to give us the TV system we know today. In the 1920s, Scotsman John Logie Baird (1888–1946) made a mechanical TV sending and receiving system using a spinning-disc scanner originally invented by a young German named Paul Nipkow (1860–1940). Electronic TVs were perfected by Russian-born Vladimir Zworykin (1888–1982), working in the United States, and Philo Farnsworth (1906–1971), who developed the modern idea of scanning, electronic television.

The first TV broadcasts were made in 1927 (by the BBC in London) and 1930 (by RCA and NBC in the United States). Though early broadcasts were made in monochrome (black and white), color TV was soon developed by Hungarian-born Peter Goldmark (1906–1977), working in the United States, also in the 1930s. [16]

Sponsored links

The sound of music

So much for pictures, but what of sounds? Let's press the rewind button on history, for a moment, to discover a different, parallel story...

By the mid-16th century, humans had mastered the art of writing down thoughts and ideas and reproducing them in quantity, but sound was a different matter. There was no obvious way to record spoken language, music, or any other kind of sound—and none would come along for at least another 200 years. Indeed, it was not until 1877 that Thomas Edison, who had experimented with telegraphs and made a number of improvements to their design, figured out a crude way of recording sound—in the shape of his "talking machine." It featured cylinders covered with foil on which a metal needle rested loosely. When you spoke into a horn, the vibrations made the needle jump up and down, cutting into the foil, which was slowly rotated to leave a groove and a record of your voice. Running the process in reverse turned the bumps in the groove back into (very crackly) sound that you could hear if you put your ear near the same horn.

Photo: Emile Berliner (1851–1929) pictured around 1927 with one of his gramophones. Photo by Harris & Ewing courtesy of US Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Edison's sound-recording machine led to the gramophone, invented by Emile Berliner (1851–1929), who used a similar needle that cut its grooves into wax-covered discs. Gradually, these evolved into vinyl plastic long-playing (LP) records that many music fans still listen to to this day, first introduced by CBS records in 1948. Plastic LPs were cheap and easy to reproduce in their thousands and millions, so ushering in the 20th-century era of mass-produced pop and rock records. But, unlike with Edison's original recorder, you couldn't record your own.

Analog and digital

This left a gap in the market that was filled by magnetic sound-recording technologies. The first of these appeared in 1888, a decade after Edison's original machine, in the shape of magnetically coated cloth tape, invented by another US inventor, Oberlin Smith (1840–1926). A German named Fritz Pfleumer (1897–1945) reinvented essentially the same idea, several decades later, before selling it to the AEG company, who began manufacturing the first tape recorders in the 1930s. Three decades later, in 1964, Philips devised a way of miniaturizing reels of tape and packaging them in convenient plastic, "compact cassettes." With a cassette recorder, you could play back other people's music and record your own sounds too. By the 1980s, thanks to Sony's Akio Morita (1921–1999), the technology was small and light enough to carry in your pocket—in the shape of the company's famous Walkman. [17]

Photo: This typical personal music player from the 1990s could play digital, optical CDs (loaded at the front) or analog, magnetic "compact cassettes" (loaded at the back).

Today, most of these forms of sound recording and playback have been superseded by digital technologies, which store sounds not as bumps in vinyl or magnetized "domains" on long reels of tape but long strings of binary numbers. In the 1960s, James T. Russell (1931–) of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory invented the basic optical technology behind the compact disc (CD), a fraction the size of an LP, which stores about an hour of sound in digital form, and which later evolved into the DVD (digital video disc) for storing movies. Further developed in the 1970s, it was finally commercialized in the 1980s by Philips and Sony.

Now, in the age of the Internet, even technologies like the CD and DVD seem dated: most of us download books, music, and other forms of information instantly, as and when we need to. Thanks to a cunning technology called streaming, pioneered by Rob Glaser (1962–) of Real Networks (then Progressive Networks) in the late 1990s, you don't even need to download things before you play them. The basic idea of streaming is to play big files (things like movies and TV programs) as they're downloading, so you don't have to wait. This made possible innovations like YouTube, Netflix, the BBC iPlayer, and many similar "on-demand" broadcasting apps.

Communication meets the computer

Photo: A go-anywhere personal communicator—better known as a smartphone.

Meanwhile, throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, computers were slowly transforming themselves from giant clanking machines into tiny electronic communicators we could carry in our pockets, while the telephone network, the Internet, and radio-cellphone technology, made it possible for these machines to communicate with one another anytime, anywhere. The Internet also spawned the World Wide Web, invented by Tim Berners-Lee (1955–) in 1989, which is an online, always-open, multimedia library that gives us access to books, newspapers, music, photos, videos, and more. And that, in turn, spawned easy to use self-publishing tools like blogs, and social media sites (such as Twitter) that let us share what we think and feel in real time. The most exciting thing about the history of communications is the way everything—written words and messages, still and moving images, movies, radio and TV, telephones, and the Internet and Web—has come together and converged in tiny little devices, smartphones, which are effectively what you might call "universal personal communicators."

Scroll back through this article and you'll see that we got from writing to tweeting in about 7,000–12,000 years; and from the alphabet to the Internet in about three and half thousand. Where will communications technology take us in the next two thousand years... two hundred... or even twenty? Watch this space!