Anemometers

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: January 24, 2024.

When you hear weather forecasters warning of how fast the wind is going to blow, do you ever stop to think how they're going to measure it? Wind isn't something you can see very easily, so you can hardly time it with a stopwatch like you'd measure the speed of an Olympic sprinter or a race car! Fortunately, scientists are amazingly inventive people and they've come up with some pretty clever ways of measuring wind speed with gadgets called anemometers. Let's take a closer look at how they work!

Photo: Measuring wind speed with a three-cup, handheld anemometer. The square plate at the back is a vane that aligns itself with the wind so you can measure wind direction too. This model, used by the US Navy, is an Ames RVM 96 B capable of measuring wind speeds up to about 50 m/s (180 km/h or 112 mph). Photo by Spencer Roberts courtesy of US Navy and Wikimedia Commons.

Sponsored links

Contents

Thinking about anemometers

Some people think wind turbines are unsafe because gales and storms could make them spin dangerously fast. That's not actually true: all large wind turbines are fitted with brakes that stop them rotating if the wind blows too hard (and they have built-in anemometers to measure the speed as well). But it's certainly true that wind turbines turn faster—and generate more electricity—the harder the wind is blowing. There you have a clue to how a basic anemometer could work.

Suppose you build yourself a miniature, table-top wind turbine and connect it to an electricity generator (effectively an electric motor wired up backwards so it makes an electric current when you spin its central axle around). The faster the rotor blades turn, the quicker the generator spins, and the higher the electric current it will produce. So if you measure the current, you have a basic way of measuring the wind speed. You have to calibrate an instrument like this before you use it, of course. In other words, you'd need to know how much current is generated by a few winds of known speed. That would help you figure out the mathematical relationship between wind speed and electric current so you could figure out the speed of an unknown wind simply by measuring the current.

Mechanical anemometers

Some of the simplest anemometers work in exactly this way. They're little more than an electricity generator mounted in a sealed-up metal cylinder with an axle protruding upward from it. On top of the axle, there are several large cups that catch the wind and make the generator spin around. Propeller anemometers work in much the same way. Like miniature wind turbines, they use small propellers to power their generators instead of spinning cups. Some anemometers have what looks like a small fan in place of the cups or propeller. As the wind blows, it spins the fan blades and a tiny generator to which they're attached, which works a bit like a bicycle dynamo. The generator is connected to an electronic circuit that gives an instant readout of the wind speed on a digital display.

Photo: A handheld digital anemometer from Kestrel. The fan at the top generates magnetic impulses, which electronic circuits inside convert into a precise wind speed. The Kestrel also measures wind direction, temperature, and assorted other weather data and can export the logs it collects to a nearby computer or smartphone. Photo by Shannon Moorehead courtesy of US Air Force and DVIDS.

Some cup-style anemometers dispense with the electricity generator and, instead, count how many times the cups or fan blades rotate each second. In one typical design, some of the fan blades have tiny magnets mounted on them and, each time they make a single rotation, they move past a magnetic detector called a reed switch. When a magnet is nearby, the reed switch closes and generates a brief pulse of electric current, before opening again when the magnet goes away. This kind of anemometer effectively makes a series of electric pulses at a rate that is proportional to the wind speed. Count how often the pulses come in and you can figure out the wind speed from that.

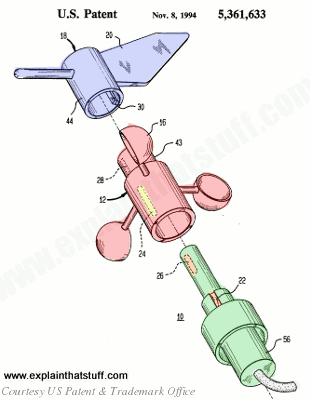

Artwork: How a simple reed-switch anemometer works. You can see it's divided into three main parts: the vane on top (blue), which indicates the wind direction; the rotating cups (red); and the stationary housing that you hold underneath (green). In the red cup section, there's a magnet built into one side (yellow). As the wind spins the cups, the magnet rotates past a couple of reed switches (orange) mounted in the stationary bottom section (green). These send impulses to a circuit that calculates the wind speed. From US Patent 5,361,633: Method and apparatus for wind speed and direction measurement by William J. Peet II, November 8, 1994, courtesy US Patent and Trademark Office.

In another design, known as optoelectronic or photoelectric (or sometimes just called a photo-chopper), spinning cups turn a kind of paddle wheel inside the metal canister underneath. Each time the paddle wheel rotates, it breaks a light beam and generates a pulse of current. An electronic circuit times the pulses and uses them to calculate the wind speed. The anemometers shown in our photos up above, made by Ames of Slovenia, work in roughly this way.

Photo: The main parts of the handheld, optoelectronic Ames anemometers used by the US Navy. The case is made of lightweight aluminum. Photo by Spencer Roberts courtesy of US Navy.

Ultrasonic anemometers

You probably know that sound travels by making air molecules move back and forth. It's fairly obvious that the speed of the wind affects the speed at which sounds travels. If you're shouting to a friend who's down-wind of where you're standing, you'll hear their voice slightly sooner than they would if there were no wind at all. Similarly, if they shout back, you'll hear their voice slightly later—because the sound waves they generate have to fight against the wind to reach you. The same idea is used in an ingenious way in ultrasonic anemometers, which measure wind speed using high-frequency sound (generally above the range humans can hear).

An ultrasonic anemometer has two or three pairs of sound transmitters and receivers mounted at right angles to one another. Stand it in the wind and each transmitter constantly beams high-frequency sound to its respective receiver. Electronic circuits inside measure the time it takes for the sound to make its journey from each transmitter to the corresponding receiver. Depending on how the wind blows, it will affect some of the sound beams more than the others, slowing it down or speeding it up very slightly. The circuits measure the difference in speeds of the beams and use that to figure out how fast the wind is blowing.

Photo: This wind-measuring mast has several anemometers mounted on it. In the center, you can just make out an ultrasonic anemometer. There are also a couple of propeller anemometers here, looking like tiny wind turbines. Photo by Warren Gretz courtesy of US Department of Energy/NREL. Artwork: An ultrasonic anemometer works by sending high-frequency sound waves (typically from about 10kHz up to 200kHz) between transmitters (blue) and receivers (pink) on three or four probes mounted on a central mast. The sound beams travel at different angles and directions, which makes it possible to calculate the wind speed very accurately.

Unlike rotating instruments, ultrasonic instruments have no moving parts, so they're less likely to fail mechanically and don't suffer quite as much from problems like freezing temperatures; they also give more accurate measurements in very high winds.

Sponsored links

Laser interferometer anemometers

Photo: A laser interferometer anemometer being used by NASA. Photo courtesy of NASA Glenn Research Center (NASA-GRC).

You can make a similar—but much more precise—measurement using beams of light instead of ultrasound. The basic principle is called interferometry, and it can be used to measure all kinds of different things with incredible precision. How does it work? You take a laser beam and split it in half using a semi-silvered mirror (a mirror partly coated with silver so it allows half the light to pass through and reflects the rest away). You keep one part of the beam intact (let's call it the reference beam) and allow the other part of the beam (let's call it the measurement beam) to be affected by the thing you want to measure. Whatever it is will slightly alter the phase (pattern of vibration) of the light waves in the measurement beam, but it won't affect the waves in the reference beam (which travel along a separate path). Now you recombine the two laser beams. The measurement beam will be slightly out of step with the reference beam, causing a strange light pattern to form where they meet and overlap, known as a set of interference fringes. By measuring the spacing of the fringes, you can calculate how much the measurement beam was affected.

When it comes to measuring air speed, you simply allow your measurement beam to pass through a chamber where the air is moving. You could fire it through part of a wind tunnel, for example, or through a pipe or tube where you're studying air flow. You need to calibrate the setup first, of course, so you know the relationship between wind speed and the changes you observe in the interference fringes. Once you've done that, you can use your laser anemometer to measure the speed of any unknown air current.

Doppler laser anemometers

Given its high-precision nature, you'd use a laser interferometer for making very precise measurements in a laboratory. But some laser anemometers are robust enough for more general use outdoors. They send one or more safe, infrared laser beams straight up into the air (which serve as the reference beam) and detect the beam reflected back down from dust particles, water droplets, and so on (which is the measurement beam). Wind movements wobble those airborne particles around so the measurement beam is slightly changed in frequency compared to the reference beam. The change in frequency is called a Doppler shift and it's much like the way a fire engine siren changes pitch from a high note to a low note as it speeds past you. By measuring the frequency shift, you can precisely measure the speed of whatever caused it (in this case, the wind speed). A typical anemometer that works in this way is the ZephIR®, made by Natural Power.

Artwork: How a Doppler laser anemometer works. A laser (1) fires through a lens (2) into a fluid (3), such as the wind, that you want to measure. Part of the beam fires through undisturbed (4), while another part (5) is scattered and Doppler shifted. Mirrors (6) recombine the beams and a photodiode (7) detects and measures them. A circuit attached to the detector figures out the wind speed from the frequency change of the recombined beams.

Hot-wire anemometers

How many more ways of measuring the wind could there possibly be? Surprisingly, quite a few. If you're familiar with the concept of wind chill, you'll know that the wind cools things as it blows past them in a very predictable way. So measuring the amount of cooling that a wind produces on an object of a certain temperature is an indirect way to figure out the speed of that wind. This is essentially how a hot-wire anemometer works. It uses an electrically heated piece of wire (similar to the filament in an old-fashioned light bulb or a thin heating element) past which the wind blows. As the wire cools, its electrical resistance changes; that can be measured (using a circuit called a Wheatstone bridge) to figure out the amount of cooling and the wind speed. Hot-wire anemometers are particularly suited for measuring turbulent air flow, and they're widely used in engineering for things like measurements of fluid flow in jet engines.

Artwork: How a hot-wire anemometer works: The cool wind (1) blows over a heated wire (2), cooling it down and changing its electrical resistance correspondingly. A Wheatstone-bridge circuit attached to the wire (3) measures its changing resistance and converts it into a more familiar measurement of wind speed.