Bullets and missiles

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: July 7, 2022.

Has any other single invention changed history quite so much as explosives? As the power behind bombs and missiles, chemical explosives have made possible most of the great wars of the last 1000 years or so, altering the course of history time and time again. Before the invention of gunpowder, the first chemical explosive, sometime in the first millennium, people had to fight their enemies hand-to-hand on the battlefield with crude weapons like swords and spears. Today, you don't even have to be able to see your enemy—let alone touch them: it's easy to drop bombs from airplanes, shoot them from submarines, or launch them on rockets from one side of the Earth to the other. But even though modern missiles are incredibly sophisticated, the basic science and technology behind them is pretty much the same as it was 1000 years ago!

Photo: A set of 5.56mm rifle bullets. Picture by Sean Clee, Royal Navy, published on Wikimedia Commons under the UK OGL (Open Government Licence).

Sponsored links

Contents

How guns fire bullets

Bullets and missiles come in all shapes and sizes. At 21.8 meters (71 ft) long, one of the world's biggest intercontinental ballistic missiles, the US Air Force LGM-118A Peacekeeper, was three times the length of a station wagon (estate car)! But it worked pretty much the same way as a handgun bullet the size of your pinkie.

What's inside a bullet cartridge?

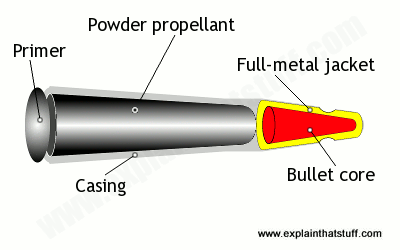

When people talk about a "bullet" in everyday language, they often mean a cartridge, which is a three-part vehicle with the actual bullet mounted on the very end. The cartridge is the thing you load into a rifle; the bullet is the part of a cartridge that fires out the end. Cartridges are a bit like fireworks and they are arranged in three sections: the primer, the propellant, and the bullet proper. At the back, the primer (or percussion cap) is like the fuse of a firework: a small fire that starts a bigger one. The next section of the cartridge, effectively the bullet's "main engine," is a chemical explosive called a propellant. Its job is to power the bullet down the gun and through the air to the target. The front part of the cartridge is the actual bullet: a tapering metal cylinder that hits the target at high speed. It tapers to a point mainly to reduce air resistance, so it goes faster and further, but also to help it penetrate metal, flesh, or whatever else the target may be made from (it must penetrate the target before it can do damage).

Artwork: The three main parts of a cartridge. 1) The primer "launches" the bullet by igniting the propellant. 2) The propellant accelerates the bullet down the gun. 3) And the bullet proper (the red and yellow bit at the end) is the part that exits the gun, flies through the air, and does the damage. This one has a complete outer casing known as a full-metal jacket, which means it can be fired faster and further, but it retains its shape on impact. Bullets with a softer point spread out on impact and do more damage, but don't travel as fast or far.

What happens when you fire?

Bullet cartridges are designed to be (relatively) safe until the moment when you fire them. When you pull the trigger of a gun, a spring mechanism hammers a metal firing pin into the back end of the cartridge, igniting the small explosive charge in the primer. The primer then ignites the propellant—the main explosive that occupies about two thirds of a typical cartridge's volume. As the propellant chemicals burn, they generate lots of gas very quickly. The sudden, high pressure of the gas splits the bullet from the end of the cartridge, forcing it down the gun barrel at extremely high speed (300 m/s or 1000 ft/s is typical in a handgun). It's only the bullet that fires from the gun; the rest of the cartridge stays where it is. It has to be ejected after firing (sometimes manually, sometimes automatically) to make way for the next cartridge—and the next shot.

Photo: Launch of a Peacekeeper missile. The backbone of the US nuclear deterrent from 1986 to 2005, the Peacekeeper was effectively a four-stage rocket, had a top speed of 24,000 kph (15,000 mph), and a range of almost 10,000 km (6000 miles). Photo by Don Sutherland courtesy of US Air Force.

The propellant chemicals in a handgun cartridge are not designed to explode suddenly, all at once: that would blow the whole gun open and very likely kill the person firing it. Instead, they are supposed to start burning relatively slowly, through a process called deflagration, so the cartridge moves off smoothly down the gun. They burn faster as the bullet accelerates down the barrel, giving it a maximum "kicking" force just as it comes out of the end. As the cartridge emerges, the whole gun recoils (leaps backward) because of a basic law of physics called "action and reaction" (or Newton's third law of motion). When the gas from the explosion shoots the bullet forwards with force, the whole gun jolts backwards with an equal force in the opposite direction.

The explosion that fires a bullet happens in the confined space of the gun barrel. As the bullet flies out of the gun, the pressure of the explosion is suddenly released. That's what makes a gun go BANG! It's a bit like uncorking a bottle of wine at much higher speed and pressure. Some bullets also make noise because they go so quickly. The fastest bullets travel at around 3000 km/h (over 1800 mph) —about three times the speed of sound. Like a supersonic (faster-than-sound) jet fighter, these bullets make shock waves as they roar through the air.

Photo: Unlike a conventional weapon, this recoilless weapon doesn't jerk back when fired. It's open at the back so the explosive blast escapes from the rear of the gun, eliminating the usual recoil. You can clearly see the heat of the explosive charge exploding from the front and the blast simultaneously shooting out from the rear. The gunner barely moves at all. Photo By Christopher Johnson, courtesy of US Army.

How bullets travel

Gun barrels have spiraling grooves cut into them that make bullets spin around very fast as they emerge. A spinning bullet is like a gyroscope: a sort of "stubborn" spinning wheel that always tries to keep turning the same way. If you try to tilt a gyroscope while it's spinning, it will try to resist whatever force you apply and, if you let go, it will soon tilt back the other way. This is why, when things are spinning, they are very hard to deflect from their path. We call this idea gyroscopic inertia or stability. A bullet behaves in exactly the same way: once it's spinning, it follows a straighter path as it goes through the air, so it's harder to deflect and much more likely to reach its target.

Photo: Do bullets really travel in straight lines? A bullet firing from a handgun looks almost like a rocket launch—and works in very much the same way. Picture by Tech. Sgt. Larry E. Reid Jr. courtesy of US Air Force..

We think of bullets flying in perfectly straight lines—but nothing could be further from the truth. Several different forces act on a bullet as it goes through the air. Over very short distances, bullets do follow more or less a straight line. Over longer distances, they follow a slight downward curve because gravity tugs them toward the ground as they go along. Air resistance and the spinning, gyroscopic motion of a bullet complicate things too. Usually, because of recoil, the person firing wobbles the gun slightly when the bullet emerges. When all these factors—the bullet's motion, gravity, air resistance, recoil, and spinning—add together, they make a bullet follow a very complicated corkscrew path as it flies through the air.

Sponsored links

Why bullets do damage

Photo: Close-up of a bullet hole in the fuselage of a US Air Force plane, fired on while delivering relief supplies in Somalia. Picture by TSgt. Val Gempis courtesy of US Air Force.

A moving object has momentum, which is the product of its mass and its velocity. The faster something moves and the heavier it is, the more momentum it has. A truck trundling along slowly has a lot of momentum because it weighs so much. Even though bullets are tiny, they have lots of momentum because they go so fast. And because they go fast, they also have huge amounts of kinetic energy, which they get from the chemical energy of the burning propellant. (Remember that kinetic energy is related to the square of an object's velocity—so if it goes twice as fast, it has four times the energy.)

Bullets do damage when they transfer their energy to the things they hit. The faster something loses its momentum, the more force it produces. (One way to define force is as the rate at which an object's momentum changes.) A rifle bullet coming to a stop in a tenth of a second produces as much force as a heavy, slow moving truck coming to rest in 10 seconds. Imagine being hit by a truck—and you'll have some idea why bullets do so much damage!

Photo: Now that's what I call kinetic energy! This is what happens when you fire a 7g (0.25 oz) projectile at a velocity of 25,000 km/h (16,000 mph) into a cast aluminum block. This huge hole has been made by something weighing about as much as an iron nail! Even if something is that tiny, if it's traveling at very high speed it will have enough kinetic energy to do a lot of damage. Photo by R.D. Ward courtesy of Defense Imagery.

More energy = more damage?

It's easy to conclude from this that a bullet needs to have as much energy as possible to do the maximum amount of damage but, unfortunately, it's not quite that simple. A rifle bullet has many times the velocity and kinetic energy of a handgun bullet, so much so that it will typically enter one side of a target, whiz straight through, and fly out the other side. If a bullet leaves the target at high speed, it's taking valuable energy with it. So what we really want from a bullet is that it deposits as much energy as possible inside the target, either stopping entirely without exiting or leaving with the minimum possible velocity. There are various ways to achieve this.

The crudest way is for a bullet to expand as it enters the target. A bullet that expands has a bigger cross-sectional area, so it creates a bigger hole (or wound) in the target. It takes more energy to make a bigger hole in something: we need to use more force over the same distance, so we say the the bullet "does more work" and uses more energy in the process. Bullets can be designed to expand by making them hollow at the pointed end and, after impact, they expand and squash down into a shape that looks like a button mushroom; that's why deforming bullets are called hollow-point or mushrooming bullets (Dum-Dum bullets is another common name for them, taken from the place in India where they were invented in the late 19th century). International law has restricted the use of expanding bullets like this in wartime since 1899, but some police forces do still use them. That's partly because expanding bullets do so much damage that they immediately incapacitate their target, but also because a mushrooming bullet, fired in self-defense (maybe in a crowded city street), is much more likely to stay inside its target and less likely to injure an innocent bystander by accident. Soft-point bullets work in a similar way, only using a soft lead tip instead of a hollow point, but expand more slowly and typically penetrate deeper.

Chart: Different types of bullets carry very different amounts of energy. With small bullets and relatively modest muzzle velocities, handguns are the least energetic weapons. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a Browning Machine Gun (BMG) .50 cartridge weighing about 50g (1.7oz) and traveling at about 900m/s (2000mph) carries almost 20,000 joules of energy—about 50–100 times more than a small handgun bullet. Chart data from various sources including "Ch3: Mechanisms of Injury/Penetrating Trauma" by J. Christopher DiGiacomo and James F. Reilly in The Trauma Manual by Andrew B. Peitzman (ed). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.