Clothes washing machines

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: January 14, 2022.

If there's one household appliance most of us simply could not do without, it's the clothes washer. If you've ever been without your machine for a few days or weeks, you'll know just how hard it is to wash clothes by hand. Although clothes washers look pretty straightforward, they pull off a really clever trick: with the help of detergents, they separate the dirt from your clothes and then rinse it away. But how exactly do they work?

Photo: European clothes washing machines like this are usually front-loaders: you put your clothes into that little circular window at the front. In the United States and Asia, top-loading machines are more common. Front- and top-loaders work a bit differently, as described below.

Sponsored links

Contents

The parts of a clothes washer

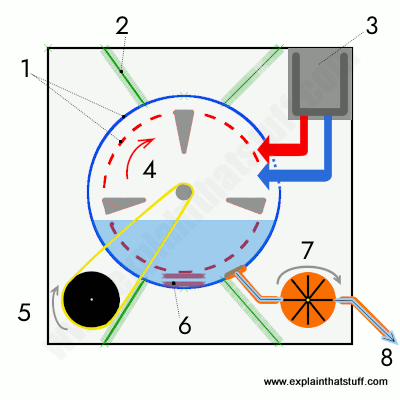

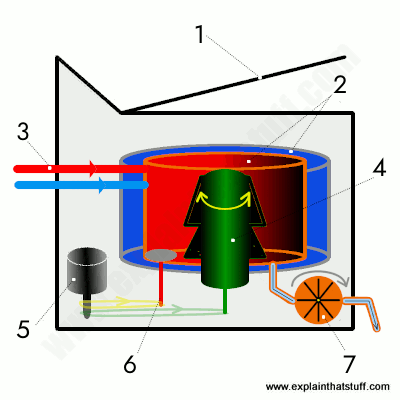

The basic idea of a clothes washer is simple: it sloshes your clothes about in soap suds for a while and then spins fast to remove the water afterward. But there's a bit more to it than that. Think of a clothes washer and you probably think of a big drum that fills with water—but there are actually two drums, one inside the other.

Photo: Inside a clothes washer drum. The paddles turn the clothes through the water. The holes let the water in (from above) and out (from below). The rubber seal (gasket) stops water leaking out through the door.

The inner drum is the one you can see when you open the door or the lid. In a front-loading clothes washer, common in Europe, the drum faces forward. You push your clothes inside the door from the front and the whole drum rotates about a horizontal axis (like a car wheel). The drum has lots of small holes to let water in and out and paddles around the edge to slosh the clothes around. In a toploader, more common in the United States and Asia, you open a lid on top and drop your clothes into the drum from above. The drum is mounted about a vertical axis but doesn't actually move. Instead, there's a paddle in the middle of it called an agitator that turns the clothes around in the water.

Photo: Clothes washing from yesteryear. This GEC electric washing machine, dating from 1935, was much more primitive than today's machines. There was no spinning to get the clothes dry: instead, you had to use a wringer (also called a mangle) fitted to the top of the machine (a pair of rollers through which you fed the clothes to squeeze out the excess water). This one is an exhibit at Think Tank, the science museum in Birmingham, England.

There's a second, bigger drum outside the inner drum that you cannot see. Its job is to hold the water while the inner drum (in a front-loader) or the agitator (in a toploader) rotates. Unlike the inner drum, the outer drum has to be completely water-tight—or you'd have water all over the floor!

The two drums are the most important parts of a clothes washer, but there are lots of other interesting bits too. There's a thermostat (thermometer mechanism) to test the temperature of the incoming water and a heating element that warms it up to the required temperature. There's also an electrically operated pump that removes water from the drum when the wash is over. There's a mechanical or electronic control mechanism called a programmer, which makes the various parts of the clothes washer go through a series of steps to wash, rinse, and spin your clothes. There are two pipes that let clean hot and cold water into the machine and a third pipe that lets the dirty water out again. All these pipes have valves on them (like little doors across them that open and shut when necessary).

The washing machine program

Photo: Controlling a washing machine: Top: An old-style mechanical clothes washer programmer. The dial on the left selects the program. The dial on the right sets the wash temperature (it's effectively a thermostat). Bottom: A modern electronic programmer. These dials are mounted on a computerized programmer circuit. The countdown-display tells you how long in hours and minutes it will be before your washing is clean and ready to take out (one hour and two minutes in this case, for a 30°C wash with a very fast 1400rpm spin).

All the important parts of the clothes washer are electrically controlled, including the inner drum, the valves, the pump, and the heating element. The programmer is like the conductor of an orchestra, switching these things on and off in a sensible sequence that goes something like this:

- You put your clothes in the machine and detergent either in the machine itself or in a tray up above.

- You set the program you want and switch on the power.

- The programmer opens the water valves so hot and cold water enter the machine and fill up the outer and inner drums. The water usually enters at the top and trickles down through the detergent tray, washing any soap there into the machine.

- The programmer switches off the water valves.

- The thermostat measures the temperature of the incoming water. If it's too cold, the programmer switches on the heating element. This works just like an electric kettle or water boiler.

- When the water is hot enough, the programmer makes the inner drum rotate back and forth, sloshing the clothes through the soapy water.

- The detergent pulls the dirt from your clothes and traps it in the water.

- The programmer opens a valve so the water drains from both drums. Then it switches on the pump to help empty the water away.

- The programmer opens the water valves again so clean water enters the drums.

- The programmer makes the inner drum rotate back and forth so the clean water rinses the clothes. It empties both drums and repeats this process several times to get rid of all the soap.

- When the clothes are rinsed, the programmer makes the inner drum rotate at really high speed—around 80 mph (130 km/h). The clothes are flung against the outside edge of the inner drum, but the water they contain is small enough to pass through the drum's tiny holes into the outer drum. Spinning gets your clothes dry using the same idea as a centrifuge.

- The pump removes any remaining water from the outer drum and the wash cycle comes to an end.

- You take your clothes out and marvel at how clean they are!

- But there's still the problem of drying your wet clothes to figure out.

Artwork: Cooling down: In the United States, it's common to wash clothes at fairly low temperatures. In Europe, warmer washing is much more the norm. This chart shows the broad trend in Germany over the last few decades, where 40°C is the typical average wash temperature. New European energy-efficiency regulations and better detergents will increasingly favor lower temperatures (20°C) in the future. [Compiled from a variety of market research sources.]

Why do washing machines need so many programs?

Your machine doesn't know what you put into it and can't automatically tell how carefully to wash something like a delicate woollen jumper—because it doesn't know that's what it's got to do! The only things under its control are the amount and temperature of the water, the speed of the spin, the number of times the drum oscillates, the number of rinses, and so on. No-one wants to wash clothes in a scientific way: "I think I need 5.42 litres of water at exactly 42°C, I'll need to wash for exactly 34 minutes, and I'll need 200 spin revolutions when I'm done." That would give us literally an infinite number of possibilities, which is too much like hard work. Recognizing this, machine engineers try to make life easy by offering a few preset programs: each one uses a slightly different combination of these variables so it washes safely within the tolerance of different fabrics.

Why does that matter? All fabrics are different. A fabric like wool is immensely strong but has two big drawbacks (from the point of getting it clean): it's extremely hygroscopic (absorbs huge amounts of water) and loses its elasticity as the temperature increases. So if you're designing a washing machine to wash woollens, that's your starting point: don't allow the wool to become too hot (because the fibers will degrade and stretch too much) and don't agitate it excessively because it will stretch and not return to shape. With sturdier fabrics like denim, you can afford to bash them about in the drum much more—indeed, you must do so, because you need the agitation to get the detergent deep into the fibers and break up the dirt (and, of course, clothes made from denim are more likely to get dirtier than more delicate fabrics such as cashmere jumpers, which people treat more carefully).

Each program you find marked on a clothes washing machine is a best guess by the engineers as to how much agitation a particular garment/fabric is likely to need and how much it can put up with without getting damaged. If you were handwashing in a sink, you'd make those judgements instinctively, balancing the need to get your garment clean with the need to protect it from damage. While your brain/hands would do that without thinking, the washing machine does it with a certain wash temperature, so many agitations, so many spins, and a certain spin speed.

Artwork: Clothes washing machines haven't always used rotating drums powered by electricity. This one, from the 1880s, is entirely mechanical and uses a large, stationary tank (light blue) with holes perforated in its base. Underneath the tank, there's a water pump (dark blue) with a piston (red) inside. As you move the handle (brown) from side to side, the pumping piston slides back and forth, alternately shooting water up into one side of the clothes container and pulling it down through the other side (yellow arrows). According to Gifford, it was a "simple and durable construction, capable of throughly washing the clothes without subjecting them to undue friction, and wherein the action of the washer will not tend to remove any buttons." From US Patent 409,399: Washing Machine by Hiram H. Gifford. Artwork courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

But do machines really need so many programs?

Look at the programmers in the photos above and you'll see something interesting: both machines seem to have an incredible number of programs. The mechanical programmer in the top photo offers 14 programs, seven temperatures, two spin speeds, and full or half load—and if you multiply those you'll get 392 possibilities! The electronic programmer underneath it offers 12 programs, 5 spin speeds, and various other options so, again, a good few hundred possibilities. Yet if you're like me, you probably wash almost all your clothes on a single program all the time. Even if you don't do that, it's unlikely you could think of 392 different types of clothing that need washing in 392 different ways.

Much of this is a marketing con to make you believe the machine has more features than it really does. Most machines can really do only about three or four basic washes: 1) a high-temperature, long-duration wash for white laundry that uses a fairly high spin speed and lots of water; 2) a slightly faster, lower-temperature wash for colored cottons that uses similar spin speed and water volume; 3) a synthetics wash that uses the same amount of water, agitates the laundry less, spins more slowly, and uses lower temperatures; and 4) a woollens wash that probably uses quite a bit more water, but agitates the drum less, and spins the water out relatively slowly. Any other programs are variations of these four.