Space rockets

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: September 28, 2023.

The most exciting thing you can possibly do on Earth is to get away from it: jump in a rocket and blast into space! Rockets always seem to be firing us into the future, but their basic technology is rooted far in the past—in firework-like missiles developed almost 800 years ago in 13th-century China. Since the first modern liquid-fueled rocket soared to the sky in 1926, rockets have ferried about 500 people, several thousand satellites, and quite a few unmanned probes to the deep darkness beyond Earth. While exploring space is obviously the main point of all that effort, it's worth remembering that "stepping outside" Earth gives us a better understanding of our own planet: weather forecasting, climate research, and navigation are just three of the things we can do better thanks to the development of the space rocket. Now rockets are useful things, but they're also very complex and highly dangerous. How exactly do they work? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: Looking up at the base of a Saturn V rocket like the ones that put astronauts on the Moon in the 1960s. The five red things are the five engines of the lowest rocket stage (technically called S-IC). Picture courtesy of NASA.

Sponsored links

Contents

What exactly is space?

Photo: Space as we know it. Photo of stellar swarm M80 (NGC 6093), a dense star cluster in the Milky Way galaxy, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and courtesy of NASA on the Commons.

If you want to understand space rockets, you need to understand space.

Strapped to your rocket, whistling your way to the stars, you won't pass any road signs: "Space: Population 0, Please drive carefully." There's no neat dividing line between the end of Earth and the beginning of space. That's because gravity (the force that sucks air molecules toward our planet, creating Earth's atmosphere) reaches out to infinity. In other words, Earth's atmosphere ends gradually, blurring invisibly with the start of space.

Where does space start?

Most jet planes don't fly above 15km (9.5 miles, 50,000ft), where there's still enough oxygen to burn fuel in their engines and keep them flying, but that's nowhere near the start of space. Space is generally defined as starting at about 100km (60 miles) above Earth (an arbitrary point sometimes called the Kármán line), which is where conventional planes would struggle to make enough lift to stay in the air. That doesn't mean Earth's atmosphere is all done and dusted by that point; far from it! The lowest satellites (known as low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites) fly at heights above 160km or 100 miles from Earth, which is over 10 times higher than planes fly. Even so, they still feel some drag (aerodynamic resistance) from the outer reaches of our atmosphere, which fizzles on up to 800km (500 miles) or higher.

You might think space is a long way away, but a hundred kilometers is not so far: a car, hurtling along at highway speed, would take just an hour to get you there; a rocket will get there about 20 times faster—in just 3 minutes.

What is space like?

From the point of someone designing a rocket, space is the place effectively beyond Earth's reach—beyond most of its gravity and atmosphere. Although we tend to think of it as a vacuum, it's not completely empty. There's radiation zipping through it (there must be—how else would we see all those distant stars and planets?), meteorites nipping past, "cosmic dust," and even bits of space junk (broken bits of satellites and rockets). Perhaps the best way to think of space is as a place of wild extremes: emptiness, weightlessness (when you're far from any planets). One minute, deep darkness and extreme cold (when you're shaded from the sun); the next, blinding light, dangerous cosmic radiation, and extreme heat.

Is there more than one kind of space?

Mostly we're interested in the interplanetary space of our own Solar System (the area round the Sun), which is measured in distances of millions of kilometers. But space telescopes and unmanned probes also study the further reaches of what's called interstellar space (the space between stars), measured in vastly greater distances called light years (the distance light travels in one year, which is almost 10 trillion kilometers). The Milky Way galaxy, of which our solar system is just one part, measures about 100,000 light years (1 million, million, million km) across.

Space, if you haven't figured it out already, is a pretty big place!

How do rockets work?

Photo: An Atlas Centaur rocket launches a scientific satellite in 1990. Picture courtesy of NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (NASA-MSFC).

Now we know what space is, it's easier to understand what a rocket is and how it works.

A space rocket is a vehicle with a very powerful jet engine designed to carry people or equipment beyond Earth and out into space. If we define space as the region outside Earth's atmosphere, that means there's not enough oxygen to fuel the kind of conventional engine you'd find on a jet plane. So one way to look at a rocket is as a very special kind of jet-powered vehicle that carries its own oxygen supply. What else can we figure out about rockets straight away? They need great speed and a huge amount of energy to escape the pull of gravity and stop them tumbling back down to Earth like stones. Vast speed and energy mean rocket engines have to generate enormous forces. How enormous? In his famous 1962 speech championing efforts to go to the Moon, US President John F. Kennedy compared the power of a rocket to "10,000 automobiles with their accelerators on the floor." According to NASA's calculations, the Saturn V moon rocket "generated 34.5 million newtons (7.6 million pounds) of thrust at launch, creating more power than 85 Hoover Dams."

Forces

Rockets are great examples of how forces make things move. It's a common mistake to think that rockets move forward by "pushing back against the air"—and it's easy to see that this is a mistake when you remember that there's no air in space to push against. Space is literally that: empty space!

When it comes to forces, rockets perfectly demonstrate three important scientific rules called the laws of motion, which were developed about 300 years ago by English scientist Isaac Newton (1642–1727).

- A space rocket obviously doesn't go anywhere unless you start its engine. As Newton said, still things (like rockets parked on launch pads) stay still unless forces act on them (and moving things keep moving at a steady speed unless a force acts to stop them).

- Newton said that when a force acts on something, it makes it accelerate (go faster, change direction, or both). So when you fire up your rocket engine, that makes the force that accelerates the rocket into the sky.

- Rockets move upward by firing hot exhaust gas downward, rather like jet planes—or blown-up balloons from which you let the (cold) air escape. This is an example of what's often called "action and reaction" (another name for Newton's third law of motion): the hot exhaust gas firing down (the action) creates an equal and opposite force (the reaction) that speeds the rocket up. The action is the force of the gas, the reaction's the force acting on the rocket—and the two forces are of equal size, but pointing in opposite directions, and acting on different things (which is why they don't cancel out).

Photo: Action and reaction: rockets work by firing jets of hot gas downward (the action), which makes them move upward (the reaction). The gas isn't pushing against anything to make the rocket move: the very act of the gas shooting back moves the rocket forward—and that can happen in "empty" space just as well as inside Earth's atmosphere. This picture shows Space Shuttle mission STS-26 in 1988, when the Shuttle made its brave and confident return to space after the Challenger disaster two years earlier. Photo courtesy of NASA on the Commons.

Thrust and drag

The force that pushes a rocket upward is called thrust; it depends on the amount (mass) and speed of gas that the rocket fires and the way its exhaust nozzle is shaped to squirt out that gas in a high-pressure jet. When a rocket's engine develops enough power, the thrust force pushing it upward will be bigger than its own weight (the force of gravity) pulling it down, so the rocket will climb into the sky. As the rocket climbs, air resistance (drag) will try to pull it back too, fighting against the thrust. In an upward-climbing rocket, thrust has to fight both drag and weight. This is slightly different to an airplane, where thrust from the engines makes the plane fly forward, drag pulls the plane backward, and the forward motion of air over the wings generates lift, which overcomes the plane's weight. So a key difference between a rocket and a jet plane is that a rocket's engine lifts it directly upward into the sky, whereas a jet's engines simply speed the plane forward so its wings can generate lift. A plane's jet engines fire it forwards so its wings can lift it up; a rocket's engines lift it up directly.

The faster things move and the more their shape disturbs the air, the more drag they create and the more energy they waste, uselessly, as they speed along. That's why fast-moving things—jet airplanes, high-speed trains, space rockets... and even leaping salmon—tend to be long, thin, and tube-shaped, compared to slower-moving things like boats and trucks, which are less affected by drag.

Artwork: Forces acting on a plane (left) and a rocket (right). When a plane flies at steady speed, the forward thrust made by the engines is equal to the air resistance (drag) pulling back. The upward force of lift created by the wings is equal to the downward force of the plane's weight. In other words, the two pairs of forces are in perfect balance. With a rocket, thrust from the engines pushes upward while weight and drag try to pull it back down. When the rocket accelerates upward, the thrust is greater than the combined lift and drag. The various surfaces of a rocket can also produce lift, just like the wings of a plane, but it acts sideways instead of upwards. Although this sounds confusing, it's easy to see why if you imagine the blue plane rotated through 90 degrees so it's flying straight up like a rocket: the lift would also be pointing sideways.

Escape velocity

Rockets burn huge amounts of fuel very quickly to reach escape velocity of at least 25,000 mph (7 miles per second or 40,000 km/h), which is how fast something needs to go to break away from the pull of Earth's gravity. "Escape velocity" suggests a rocket must be going that fast at launch or it won't escape from Earth, but that's a little bit misleading, for several reasons. First, it would be more correct to refer to "escape speed," since the direction of the rocket (which is what the word velocity really implies) isn't all that relevant and will constantly change as the rocket curves up into space. (You can read more about the difference between speed and velocity in our article on motion). Second, escape velocity is really about energy, not velocity or speed. To escape from Earth, a rocket must do work against the force of gravity as it travels over a distance. When we say a rocket has escape velocity, we really mean it has at least enough kinetic energy to escape the pull of Earth's gravity (though you can never escape it completely). Finally, a rocket doesn't get all its kinetic energy in one big dollop at the start of its voyage: it gets further injections of energy by burning fuel as it goes. Quibbles aside, "escape velocity" is a quick and easy shorthand that helps us understand one basic point: a huge amount of energy is needed to get anything up into space.

Sponsored links

Parts of a space rocket

A rocket contains about three million bits, of all shapes and sizes, but it's simpler to think of it as being made up of four separate parts. There's the structure (the framework that holds the whole thing together, similar to the fuselage on a plane), the propulsion system (the engine, fuel tanks, and any outer rocket boosters), the guidance system (the onboard, computer-based navigation that steers the rocket to its destination), and the payload (whatever the rocket is carrying, from people or satellites to space-station parts or even nuclear warheads). Modern space rockets work like two or three independent rockets stuck together to form what are called stages. Each stage may have its own propulsion and guidance system, though typically only the final stage contains the rocket's all-important payload. The lower stages break away in turn as they use up their fuel and only the upper stage reaches the rocket's final destination.

Some rockets (the Space Shuttle and the European Ariane) look like a whole bunch of rockets "strapped" together: a fat one in the middle with some skinnier ones either side. The big central rocket is the main one. The thinner rockets either side are what are called booster rockets. They're little more than fat fireworks: disposable engines that provide a thump of extra power during liftoff to get the main rocket up into space.

Artwork: Little pieces of history: An interesting cutaway showing the main component parts of the now-retired Space Shuttle orbiter. Picture courtesy of NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (NASA-MSFC). Browse the hi-resolution version of this image (via Wikimedia Commons).

Rocket engines

Photo: Test firing the Space Shuttle's main engine. Picture courtesy of NASA on the Commons.

The biggest (and arguably the most interesting) part of a rocket is the propulsion system—the engine that powers it into the sky. As we've already seen, rockets differ from jet planes (and other fuel-powered vehicles that work on Earth) because they have to carry their own oxygen supply. Modern space rockets have main engines powered by a liquid fuel (such as liquid hydrogen) and liquid oxygen (which does the same job as the air sucked into a car engine) that are pumped in from huge tanks. The fuel (also called the propellant) and oxygen (called the oxidizer) are stored at low temperatures and high pressures so more can be carried in tanks of a certain size, which means the rocket can go further on the same volume of fuel. External rocket boosters that assist a main rocket engine typically burn solid fuel instead (the Space Shuttle's were called solid rocket boosters, or SRBs, for exactly that reason). They work more like large, intercontinental ballistic missiles, which also burn solid fuels.

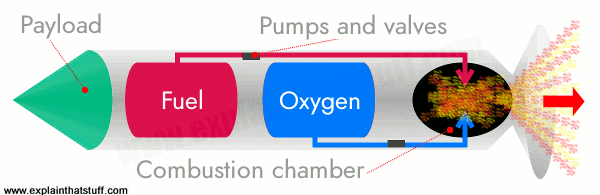

Artwork: How a space rocket works—greatly simplified: Unlike airplane jet engines, which take in air as they fly through the sky, space rockets have to carry their own oxygen supplies (oxidizers) with them because there is no air in space. Liquid hydrogen (the fuel) from one tank is mixed with liquid oxygen (the oxidizer) from a separate tank using pumps and valves to control the flow. The oxidizer and fuel mix and burn in the combustion chamber, making a hot blast of exhaust gas that propels the rocket. The payload (the cargo—such as a satellite) occupies a relatively small proportion of the rocket's total volume in the nose-cone at the top.

A typical space rocket: Ariane 5

How many space rockets can you name? The mighty Saturn V that took astronauts to the Moon is probably top of your list. Or what about the super-versatile Atlas rockets? The first one took off on June 11, 1957 and the latest version, Atlas 5, is still blasting off today. The highlights of that half-century history include putting the first US astronaut into space, sending the Pioneer-10 space probe to Jupiter and beyond, and launching the ten Mariner program missions to explore Mars, Venus, and Mercury.

Outside the United States, there's the European Ariane rocket. Originally dreamed up in 1973 as a joint project between France, Germany, and the UK, it's gradually established itself as one of the most reliable of rockets, launching over half of the world's commercial satellites from its base on French Guiana. The latest version, Ariane 5, has launched about 90 times since its maiden voyage in 1996 (with only two major failures).

Photo: An Ariane 5 rocket waiting to launch the James Webb Space Telescope. Picture by Chris Gunn courtesy of NASA and Wikimedia Commons.

Key parts of an Ariane rocket

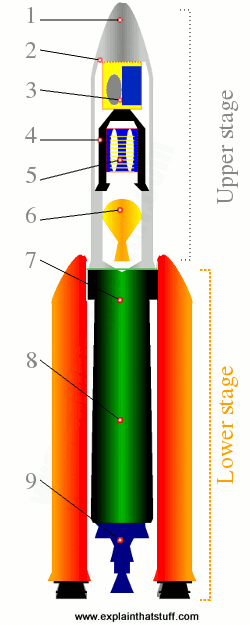

Sitting on the launchpad, Ariane has three main parts: the central rocket (up to 53m or 174ft high), powered by the main engine (Vulcain 2), and two 31m/101ft-high solid rocket boosters (one either side). The main rocket consists of two stages. The first (lower) stage is called the Cryogenic Main Stage (or EPC). Powered by the Vulcain engine, and assisted by the two SRBs, its job is to get the rocket and its payload out of Earth's atmosphere and into space. The second (upper) stage is called the Cryogenic Upper Stage (ESC-A). It's powered by a much smaller engine called Aestus, which produces a tiny 2.6 tonnes of thrust, just enough to put the rocket into its final orbit ready for the release of the satellites it carries as payload. The payload travels in the very top part of the rocket behind a detachable fairing (streamlined outer cover) that measures 17m high by 5.4m in diameter (56ft high by 18ft in diameter). The usual payload is either one or two satellites fixed either side of a launching structure called the Speltra (or a slightly different one called the Sylda).

Artwork: The parts of an Ariane 5 rocket. The central rocket comprises two stages: the lower Cryogenic Main Stage (EPC, orange dotted line) and the Cryogenic Upper Stage (ESC-A, gray dotted line). Solid rocket boosters (orange) stand on each side. Inside the central rocket, the main parts are: 1) Detachable fairing to protect payload as the rocket blasts through Earth's atmosphere; 2) Payload consisting of (in this mission) two satellites to be launched; 3) Satellite mounted on top is launched last; 4) Speltra structure allows two satellites to be launched in the same mission; 5) Satellite mounted underneath Speltra is launched first; 6) Small Aestus engine; 7) Liquid oxygen tank; 8) Liquid hydrogen tank; 9) Vulcain main engine.

A typical Ariane mission

It takes Ariane less than an hour to put two satellites into space:

- Liftoff: At liftoff, the rocket weighs up to 780 tonnes (as much as about 500 cars), of which the payload represents 10 tonnes at most. In other words, the cargo represents just 1 percent of the total weight! To put this huge mass into space, Ariane 5 has to produce a total of about 1340 tonnes of thrust: 1200 from the two SRBs (600 each) and 140 from the Vulcain engine. At liftoff, the Vulcain fires first; the SRBs start up a few seconds later.

- SRBs jettisoned: The SRBs fire for about two and a half minutes before separating from the main stage when it reaches an altitude of about 69km (42 miles). The SRBs reenter Earth's atmosphere, then fall into the Atlantic Ocean.

- Payload fairing jettisoned: Once the rocket is safely outside Earth's atmosphere, about three minutes after launch and an altitude above 100km (62 miles), explosive (pyrotechnic) charges split the protective payload fairing apart and it's jettisoned.

- Cryogenic main engine jettisoned: The main Vulcain engine fires for about nine minutes in total (from the launch), during which time it burns 25 tonnes of liquid hydrogen and 150 tonnes of liquid oxygen. At a height of about 200km (124 miles), the main stage (EPC) shuts down and is jettisoned from the rest of the craft. It reenters Earth's atmosphere, also destined for the ocean.

- Upper stage moves into orbit: The upper stage engine (ESCA) ignites and positions the remainder of the rocket in orbit before shutting down roughly 25 minutes into the mission at an altitude of 640km (400 miles).

- First satellite separates: Just over 27 minutes into the mission, the first satellite splits away from the Speltra and maneuvers itself into orbit, leaving the second satellite still attached to the launch vehicle.

- Second satellite separates: About 35 minutes into the mission, the second satellite splits away from the Speltra and maneuvers into orbit.

- End of mission: The entire mission takes roughly 50 minutes from launch to completion.