Inventors and inventions

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 16, 2023.

Have you ever dreamed of becoming a great inventor—of having a fantastically clever idea that changes society for the better and makes you rich in the process? The history of technology is, in many ways, a story of great inventors and their brilliant inventions. Think of Thomas Edison and the light bulb, Henry Ford and the mass-produced car, or, more recently, Tim Berners-Lee and the World Wide Web. Inventing isn't just about coming up with a great idea; that's the easy part! There's also the matter of turning an idea into a product that sells enough to recoup the cost of putting it on the market. And there's the ever-present problem of stopping other people from copying and profiting from your ideas. Inventing is a difficult and often exhausting life; many inventors have died penniless and disappointed after struggling for decades with ideas they couldn't make work. Today, many lone inventors find they can no longer compete and most inventions are now developed by giant, powerful corporations. So, are inventors in danger of going extinct? Or will society always have a place for brave new ideas and stunning new inventions? Let's take a closer look and find out!

Listen instead... or scroll to keep reading

Artwork: Inventions are useful, practical creations of the human mind. All our minds work in roughly the same way, so it's not really surprising that different people can have similar ideas for a problem-solving invention at almost exactly the same time.

Sponsored links

Contents

What is invention?

That sounds like a trivial question, but it's worth pausing a moment to consider what "invention" really means.

In one of my dictionaries, it says an inventor is someone who comes up with an idea for the first time. In another, an inventor is described as a person of "unique intuition or genius" who devises an original product, process, or machine. Dictionary definitions like these are badly out of date—and probably always have been. Since at least the time of Thomas Edison (the mid-to-late 19th century), invention has been as much about manufacturing and marketing inventions successfully as about having great ideas in the first place.

Some of the most famous inventors in history turn out, on closer inspection, not to have originated ideas but to have developed existing ones and made them stunningly successful. Edison himself didn't invent electric light, but he did develop the first commercially successful, long-lasting electric light bulb. (By creating a huge market for this product, he created a similarly huge demand for electricity, which he was busily generating in the world's first power plants.)

Artwork: Thomas Edison's electric lamp owed much of its success to clever marketing. This wasn't the first electric light, but it was the first really practical and commercially successful one. Artwork courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In much the same way, Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi can't really be described as the inventor of radio. Other people, including German Heinrich Hertz and Englishman Oliver Lodge, had already successfully demonstrated the science behind it and sent the first radio messages. What Marconi did was to turn radio into a much more practical technology and sell it to the world through bold and daring demonstrations. These days, we'd call him an entrepreneur—a self-starting businessperson who has the drive and determination to turn a great idea into a stunning commercial success.

Photo: Guglielmo Marconi didn't so much "invent" radio as make it practical and popular. Photo courtesy of US Library of Congress.

It's important not to underestimate the commercial side of inventing. It takes a lot of money to develop an invention, manufacture it, market it successfully, and protect it with patents. In our gadget-packed homes and workplaces, modern inventions seldom do completely original jobs. More often, they have to compete with and replace some existing gadget or invention to which we've already become attached and accustomed. When James Dyson launched his bagless cyclone vacuum cleaner, the problem he faced was convincing people that it was better than than the old-fashioned vacuums they had already. Why should they spend a fortune buying a new machine when the one they had already was perfectly satisfactory? Successful inventions have to dislodge existing ones, both from our minds (which often find it hard to imagine new ways of doing things) and from their hold on the marketplace (which they may have dominated for years or decades). That's another reason why inventing is so difficult and expensive—and another reason why it's increasingly the province of giant corporations with plenty of time and money to spend.

How and why do people invent things?

According to the well-known saying, "necessity is the mother of invention"; in other words, people invent things because society has difficult problems that need solving. There's some truth in this, though less than you might suppose. It would be more accurate to say that inventions succeed when they do useful jobs that people recognize need doing. But the reasons inventions appear in the first place often have little or nothing to do with "necessity," especially in the modern age when virtually every need we have is satisfied by any number of existing gadgets and machines. Where, then, do inventions come from and why do people invent them?

Scientific breakthroughs

Artwork: The discovery of how DNA worked revolutionized crime-fighting and forensic science—and will have huge impacts on medical science and technology in the future. This picture is a simplified illustration of the DNA double helix.

Some inventions appear because of scientific breakthroughs. DNA fingerprinting (the process by which detectives take human samples at crime scenes and use them to identify criminals) is one good example. It only became possible after the mid-20th century when scientists understood what DNA was and how it worked: the scientific discovery made possible the new forensic technology. The same is true of many other inventions. Marconi's technological development of radio followed on directly from the scientific work done by Lodge, Hertz, James Clerk Maxwell, Michael Faraday, and numerous other scientists who fathomed out the mysteries of electricity and magnetism during the 19th century. Generally, scientists are more interested in advancing human knowledge than in commercializing their discoveries; it takes a determined entrepreneur like Marconi or Edison to recognize the wider, social value of an idea—and turn theoretical science into practical technology.

Trial and error

But it would be very wrong to suggest that inventions (practical technologies) always follow on from scientific discoveries (often abstract, impractical theories). Many of the world's greatest inventors lacked any scientific training and perfected their ideas through trial and error. The scientific reasons why their inventions succeeded or failed were only discovered long afterward. Engines (which are machines that burn fuel to release heat energy that can make something move) are a good example of this. The first engines, powered by steam, were developed entirely by trial and error in the 18th century by such people as Thomas Newcomen and James Watt. The scientific theory of how these engines worked, and how they could be improved, was only figured out about a century later by Frenchman Nicolas Sadi Carnot. Thomas Edison, one of the most prolific inventors of all time, famously told the world that "Genius is one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration"; he had little or no scientific training and owed much of his success to persistence and determination (when he came to develop his electric light, he tested no fewer than 6000 different materials to find the perfect filament).

Photo: Steam engines weren't developed scientifically: they evolved slowly and gradually by trial and error. As Nicolas Sadi Carnot later pointed out, they could be extremely inefficient machines—which meant they used a huge amount of fuel (coal) to power themselves. But that didn't matter in an age where coal was relatively cheap and abundant and people cared less about pollution.

Inventions that evolve

Some inventions are never really invented at all—they have no single inventor. You can comb your way through thousands of years of history, from the abacus to the iPhone, and find not a single person who could indisputably be credited as the sole inventor of the computer. That's because computers are inventions that have evolved over time. People have needed to calculate things for as long as they've traded with one another, but the way we've done this has constantly changed. Mechanical calculators based on levers and gears gave way to electronic calculators in the early decades of the 20th century. As newer, smaller electronic components were developed, computers became smaller too. Now, many of us own cellphones that double-up as pocket computers, but there's no single person we can thank for it. Cars evolved in much the same way. You could thank Henry Ford for making them popular and affordable, Karl Benz for putting gasoline engines on carts to make motorized carriages, or Nikolaus Otto for inventing modern engines in the first place—but the idea of vehicles running on wheels is thousands of years old and its original inventor (or inventors) has long since disappeared in time.

Accidental inventions

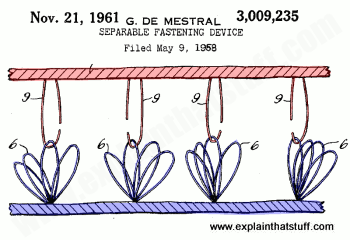

Artwork: VELCRO®: George de Mestral chanced on the idea of a clothing fastener entirely by accident. Here's a drawing from his invention US Patent 3,009,235: Separable fastening device (filed 1958, granted 1961) courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

Some inventions happen through pure luck. When Swiss inventor George De Mestral was walking through the countryside, he noticed how burrs from plants stuck to his clothes and were hard to pull away. That gave him the idea for the brilliant two-part clothing fastener that he called VELCRO®. Another inventor who got lucky was Percy Spencer. He was experimenting with a device called a magnetron, which turns electricity into microwave radiation for radar detectors (used for direction-finding in ships and planes), when he noticed that a chocolate bar in his pocket had started to melt. He realized the microwave radiation was generating heat that was cooking (and melting) the food—and that gave him the idea for the microwave oven. Teflon®, the super-slippery nonstick coating, was also discovered by accident when Roy Plunkett accidentally made some strange white goo in a chemical laboratory. Its amazing nonstick properties were only discovered and put to use later. All these inventions, and numerous others, were chance discoveries produced by accidents or mistakes.

Advantageous inventions

From IBM and Sony to Goodyear and AT&T, many of the world's biggest, best-known corporations have been built on the back of a single great invention. IBM, for example, grew out of an earlier company selling intricate mechanical census-counting machines developed by Herman Hollerith; Sony made its name selling cheap, high-quality radios made with tiny transistors; Goodyear owes its name (and its chief product) to Charles Goodyear, a hapless inventor who finally developed durable, modern, "Vulcanized" rubber after a lifetime of trial and error; AT&T can trace its roots back to the telephone patented by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876. But a modern company can't survive and thrive on one great idea alone. That's why so many companies have huge research and development laboratories where inspired scientists and engineers are constantly trying to come up with better ideas than the ones on which their original success was founded. As marketing genius Theodore Levitt pointed out in the 1960s, visionary companies need the courage to try to put themselves out of business by coming up with new products that make their existing ones obsolete; companies that rest on their laurels will be put out of business by their inventive competitors. This kind of corporate invention—companies trying to out-invent themselves and one another—is very much the way the world works now.

Sponsored links

The world of corporate invention

![Apple ][ microcomputer in a museum glass case](https://cdn4.explainthatstuff.com/appleII.jpg)

Photo: Inventors have to start somewhere: The Apple ][ computer made Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak rich and famous, but they started their lives making and selling their original Apple I in a garage belonging to Jobs' parents.

There are probably more people trying to invent things now than at any time in history, but relatively few of them are lone geniuses struggling away in home workshops and garages. There will always be room for lucky individuals who have great ideas and get rich by turning them into world-beating products. But the odds are stacked increasingly against them. It's unlikely you'll get anywhere tinkering away in your garage trying to invent a personal computer that will change the world, the way Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs did back in the mid-1970s when they put together the first Apple Computer. To do that, you'd have to set yourself up in competition with—guess who—Apple Computer (which became the world's richest company in 2011 and remains so over a decade later), staffed with legions of brilliantly creative scientists, engineers, and designers, and with billions of dollars to spend on research and development. Really prolific inventors might file a few dozen patent applications during their lifetime, if they're lucky; but the world's most inventive company, IBM, files several thousand patents every single year. Companies like IBM have to keep on inventing to keep themselves in business: inventions are the fuel that keep them going.

Photos: Nylon—the power behind your toothbrush: Could anyone develop such a fantastic material tinkering away in a garage? Not likely. In our sophisticated 21st-century world, it takes well-funded corporate research labs to come up with amazing new chemical materials like this. Read how it was developed by Wallace Carothers for DuPont in our article on nylon.

Think of inventions in the 19th century and you'll come across lone inventors like Charles Goodyear, Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, George Eastman (of Kodak)—and many more like them. But think of inventing in the 20th and 21st century and you'll come across inventive corporations instead—such companies as DuPont (the chemical company that gave us nylon, Teflon®, Kevlar®, Nomex®, and many more amazing synthetic materials), Bell Labs (where transistors, solar cells, lasers, CD players, digital cellphones, commercial fax machines, and CCD light sensors were developed), and 3M (pioneers of Scotchgard textile protector and Post-It® Notes, to name only two of their best-known products). It was Thomas Edison who transformed the world of inventing, from lone inventors to inventive corporations, when he established the world's first ever invention "factory" at Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1876.

Photo: Thomas Edison essentially invented the idea of corporate invention at his Menlo Park and (later) West Orange research labs. In recognition of its significance, West Orange is now a designated National Historical Park. This photo shows one of the West Orange machine shops where Edison and his colleagues worked on new inventions. Credit: Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

These days, corporations dominate our world, and they dominate the world of inventing in exactly the same way. If it's your dream to become a great inventor, go for it and good luck to you—but be prepared to take on some very stiff, very well-funded, corporate competition. If you succeed, congratulations: maybe you'll prove to be the founder of the next Apple, AT&T, or IBM!