Biofuels

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: July 5, 2022.

Earth scientists believe the world has just a few decades about worth of oil still buried in its rocks—but they've been saying the same thing now for... decades! Whatever the reality about "peak oil", one thing is certain: with ever-growing numbers of vehicles on our streets, oil is going to become more expensive and harder to obtain over the next few decades. That's why many people think the future lies with alternative fuels made from crops and waste products. Known as biofuels, these potentially offer many advantages over petroleum. They could help us tackle global warming and, by reducing our dependence on oil from the Middle East, they could help make the world a safer place. But biofuels have major drawbacks too. Critics think their environmental benefits are overstated and argue that, by taking land that would otherwise be used for growing food, they could severely worsen poverty and hunger in developing countries. Let's take a closer look at how biofuels work and consider some of the pros and cons.

Photo: Advanced biofuels made from algae. Photo by Dennis Schroeder courtesy of NREL, photo ID#40069. One day, every gas station could be pumping out fuel made from plants. Some already have a "Biodiesel" stand with pumps offering a choice of several common blends, including B20 (20% biodiesel and 80% ordinary diesel), E85 (85% ethanol and 15% gasoline), and E10 (10% bioethanol and 90% gasoline), also called gasohol.

Sponsored links

Contents

What are biofuels?

A fuel is something we burn to release energy in a chemical reaction called combustion, which goes like this:

Fuel + oxygen (from the air) → released heat energy + carbon dioxide (CO2) + water (H2O)

The exact chemical reaction depends on which fuel you burn, but broadly the same process is at work whether you burn natural gas in a central-heating boiler, wood on a camp fire, gasoline in a car engine, or coal in a power plant.

Almost any organic (carbon-based) substance can be a fuel. Our commonest fuels are such things as coal, oil, gas, peat, and wood—all of them made from hydrocarbons (molecules built from hydrogen and carbon atoms) and all of them ultimately derived from living things (either dead plants or animals). Strictly speaking, the word biofuel can mean any fuel made from living organisms or their waste—which means most of our fuels are biofuels. But we normally use the word "biofuels" in a much more restricted sense to talk about liquid and gas vehicle fuels made from crops or waste products. The best-known biofuels are ethanol (an alcohol made from sugar beet) and biodiesel made from vegetable oil.

Types of biofuels

Photo: Most biodiesel in the US is made from soybeans, like these, or recycled cooking oil. Photo by Scott Bauer courtesy of US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service.

Biofuels are a hot environmental topic at the moment, but they've been around for many decades. People who work with them often talk about first-, second-, and third-generation biofuels to distinguish between simple, traditional biofuels that have been used for a long time and the more complex, more advanced, and more efficient ones that are currently in development.

- First-generation biofuels include such things as vegetable oil, biodiesel, ethanol, and methanol. Ethanol and methanol are very strong alcohols made from sugar, wheat, or corn in a process similar to brewing. Vegetable oil made from such things as peanuts and soybeans can be burned directly as a fuel, or it can be turned into biodiesel, a gasoline substitute (or additive) that can help to reduce vehicle emissions.

- Second-generation biofuels are made by turning crops into liquid fuels using more sophisticated chemical processes and include such things as BioHydrogen (hydrogen gas made from crops) and mixed alcohols. They are generally more efficient than first-generation biofuels because they release more energy per volume, so you can go further on a tank filled with them. It also helps if you are growing crops to make fuels, because it means you have to grow fewer plants and cultivate less land to produce the same amount of energy.

- Third-generation ("advanced") biofuels are made using oil produced from algae, grown in ponds or closed reactors, which is refined to make conventional fuels like biodiesel, methane, ethanol, and so on. The big advantage of algae-derived fuels is that they don't need vast amounts of farmland; the big drawback is that they need lots of water and fertilizer, which greatly increases the cost and environmental impact, potentially wiping out any benefit.

Photo: In the future, will most of our biofuels be made from algae like this? Photo by Dennis Schroeder courtesy of US Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE/NREL).

What are the benefits of biofuels?

If you read the news, you'll have seen a great deal of coverage about biofuels in the last few years. The basic idea is certainly very attractive: instead of pumping oil out of the ground and shipping it round the world, we could produce biofuels from crops and waste instead. For a country such as the United States, which is hugely dependent on oil from the Middle East (the world's most politically unstable region), a plan like that has huge attractions.

How much difference could biofuels make? Organizations like the International Energy Agency have highlighted enormous potential. In its Biofuels for Transport Roadmap, published in 2011, the IEA suggested biofuels could produce 27 percent of the world's total transportation fuel by 2050 (over a 10-fold increase from today). Such an ambitious project would need 100 million hectares (Mha) of land (roughly the area of South Korea). [1]

Sounds good? There's another great benefit too.

The IEA's roadmap would reduce total world carbon dioxide emissions by 2.1Gt (a little under 10 percent of the current global total). Normally, burning fuels such as petroleum,

coal, and gas (which were made millions of years ago) releases carbon

dioxide into the air—in other words, it increases emissions.

This gas smothers Earth like a huge invisible

blanket, heats the planet—the problem we now call global warming—and is starting to

change the

climate. In theory, biofuels don't suffer from the same problem. When a

tree grows, it absorbs carbon dioxide (CO2) from the

air, and water (H2O) from the soil, and uses sunlight to

convert the carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen from these molecules into more

complex carbohydrate molecules (sugars and starches) that it stores.

This process is called photosynthesis and it's a little bit like combustion running in reverse. Through photosynthesis, a tree uses carbon dioxide to grow. If we burn the tree as a fuel at the end of its life, the process of combustion releases exactly the same amount of carbon dioxide as the tree absorbed when it grew. So biofuels are (at least in theory) carbon neutral: growing a tree (or any other plant) and then burning it as a biofuel doesn't add any carbon dioxide to the atmosphere or make global warming any worse.

Photo: As you read this, scientists are working hard to develop the next generation of biofuels. Photo by Scott Bauer courtesy of US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service.

What are the drawbacks of biofuels?

If it were only that simple, we'd be growing biofuels like crazy and switching half the planet to biofuel production tomorrow. Unfortunately, biofuels have some drastic drawbacks.

Carbon neutral?

Imagine you're a farmer. You've heard great things about biofuels and how they can help to save the planet, so you decide to convert all your fields to soybeans and produce biodiesel. You'll need energy to power your tractors to plant the fields and harvest them and more energy to ship the beans round the world. More energy will be needed to power the chemical plants that turn the beans into biodiesel and even more will be needed to transport the finished biodiesel to the vehicles that use it. Using all this energy means burning fuel and releasing carbon dioxide. You may be trying to help the planet reduce its carbon dioxide emissions, but you're actually generating quite a lot of the very gas you want to prevent in growing, processing, and transporting your crops! That means biofuels are not actually carbon neutral at all. According to research funded by the US Department of Energy, ethanol from corn produces 19–48 percent fewer carbon dioxide emissions, while cellulose-produced ethanol could reduce emissions by as much as 115 percent. But other studies have discovered that the entire process of producing biofuels can generate more carbon dioxide than the fuels themselves save (which casts considerable doubt on whether some biofuels are worth growing at all). In 2016, for example, The Guardian reported that biodiesel from palm oil produces three times the emissions of fossil fuels, while oil from soybean produced twice as much.

Who is correct? And how can ordinary consumers hope to make sense of it? One solution could be eco-labeling, in which properly sustainable biofuels are certified by a credible, independent third-party. In May 2016, The New York Times reported that Pacific Biodiesel's Hawaii plant had become the first in the United States to be granted a certificate of sustainability by the Sustainable Biodiesel Alliance.

Photo: Giant farm machines use huge amounts of energy. These tractors and harvesters at the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center run on a mixture of diesel and biodiesel made from soybeans. Photo by Bob Nichols courtesy of US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service.

Biodiversity?

Relatively little land is needed for oil rigs and pipelines compared to the size of the vast underground oil fields that they tap into (not least because many oil fields are offshore). The same is not true of biofuels: enormous amounts of land are needed to grow the crops. If you planted up a forest on top of an old strip mine and harvested the trees to make biofuels, there'd be a net benefit to the planet. But what if you felled and burned a large area of rainforest to grow palm oil for making biodiesel? Then you'd be releasing a huge amount of energy by burning the trees, the planet would no longer benefit from the trees growing and removing carbon dioxide, and we'd lose the forest's wonderful biodiversity (its dense collection of animals and plants). You might think you were making "environmentally friendly biofuel," but you'd be doing so much damage in the process that there could be an overall negative impact. This problem is already occurring in developing countries where forests are being felled (because they have no immediate financial value) to grow lucrative crops for biofuels. Mark Avery, former conservation director of the UK charity RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) and a vociferous opponent of biofuels, argues that this "threatens to accelerate the destruction of some of the world's most precious habitats and wildlife. Without environmental standards, biofuels will be little more than a green con."

Chart: Who produces the most biofuels? America (North, South, and Central) produces about two thirds of the world total. Africa, CIS (Russia and associated republics), and the Middle East combined produce less than 1 percent of the total. Inner ring shows data for 2019, middle ring shows 2020, and outer ring shows 2021. Drawn by explainthatstuff.com using data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2022, p.48.

Sponsored links

Fuel versus food?

There's only so much land in the world, but the number of people each acre has to support is increasing rapidly. As oil becomes more expensive, so biofuels become more attractive to grow. That means farmers may find they can earn more by growing biofuel crops than food crops, which could lead to food shortages and increasing food prices. People in developing countries (already with the greatest struggle for survival) will be hardest hit by any rise in the price of basic commodities such as wheat. In our haste to use biofuels to tackle global warming (one of the world's most pressing problems), it's possible we could worsen world hunger and poverty (two of the world's other pressing problems). According to Action Aid, a poverty-fighting charity, in an undated briefing they wrote around 2011 or 2012: "If biofuels targets set by the U.S. and Europe are met the amount of land used to create fuel rather than food will increase dramatically. The result? Food prices could rise by up to 76% by 2020, pushing 600 million people into hunger." [2] Since then, Action Aid has attributed significant food price increases in Mexico to the use of corn ethanol in the United States and major environment impacts to the expansion of ethanol production in Brazil. [3]

Not everyone agrees with this assessment. Some think growing biofuel crops could be a lifesaver for farmers in both developed and developing countries. According to the Organisation for Economic Development (OECD), worldwide biofuel production has tripled over the last decade. In theory, that massively growing market for agricultural produce should be great news for farmers; in practice, things aren't so simple. Growing questions over the sustainability of biofuels could see many farmers, who've invested heavily in biofuel production, left high and dry. (See, for example: New EU biofuels law could be last straw for farmers hit by wet weather and rising costs", The Guardian, October 14, 2012.)

Some argue that biofuels could bring benefits for developing countries. According to Peter Kendall, president of Britain's National Farmers Union: "What has been holding back agriculture in the developing world is not a shortage of land, but the rock-bottom prices caused by the fact that world markets have been swamped by surplus grain, from both the EU and US. If the demand for biofuels helps to change that, directly by lifting prices and indirectly by mopping up the surpluses, then it will give Third World farming the biggest single boost it has ever had. That, in turn, will do more to alleviate starvation in Africa and elsewhere than all the food aid programs put together." (Quoted in: Biofuels 'will not lead to hunger', BBC News Viewpoint, October 5, 2006).

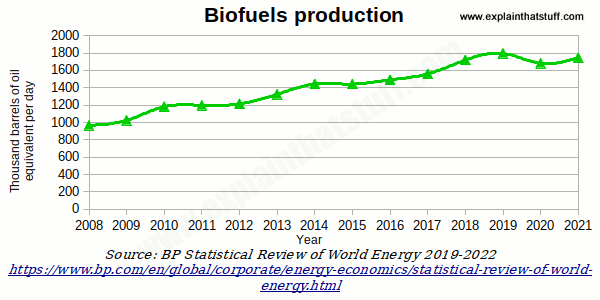

Chart: Total biofuel production has increased by about 100 percent in the last decade, with a current annual rate of growth (in 2021) of 4.1 percent (compared to 3.5 percent in 2017). Drawn by explainthatstuff.com using the latest data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2022, p.48 ("Renewables: Biofuels production") and previous annual editions.

Power to the people?

Photo: Power to the people: This truck driver could be helping save the planet by filling up with 95% ethanol, a fuel made from corn. It's just the same as filling up with ordinary diesel or gasoline, but the truck's engine has been specially modified. Photo by Warren Gretz courtesy of US Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE/NREL).

In theory, biofuels give local communities the power to grow their own fuel and lead self-sufficient, sustainable lives with little impact on the planet. There's nothing to stop anyone making their own biofuels by growing "energy crops" on their own land or producing their own biodiesel from waste products. Indeed, When Rudolph Diesel (1858–1913) invented his diesel engine in the 1890s, he envisaged people doing just this: his vision was one of local communities growing crops to run their engines and making themselves entirely self-sufficient in energy in the process. Ironically, Diesel's community-spirited ideas were quickly lost and forgotten. Today, hardly anyone makes their own fuel; virtually all diesel engines run on petroleum pumped from the ground by multinational oil companies in a centralized, globalized market. Just as huge multinationals dominate oil production, so they are already dominating the production of biofuels. Far from taking control of their own future, local communities in such places as Kalimantan, Indonesia have been forced from their land so that large companies can fell their forests, strip the land, and grow palm oil for making biodiesel. (See, for example, the Greenpeace briefing "Palm Oil").

Venture capital firms, genetic engineering corporations, oil firms, and car firms have already moved in on what they see as the next hugely lucrative business opportunity. Some would see that as a good thing. The world has a huge investment in burning oil and it will take a herculean effort (and massive investment) to switch people over to more environmentally friendly forms of power. But, on the other hand, are we simply switching all the problems of an oil-dependent economy for a different set of problems with biofuels?

Biofuels: good or bad?

On balance, then, the case for biofuels isn't nearly so clear cut as it seems. If they're produced in a responsible way, biofuels could help us cut carbon dioxide emissions and tackle global warming. But in the dash for profit, there's a risk they could lead to greater emissions and significant loss of biodiversity and exacerbate problems such as poverty and hunger in developing nations. With limited world resources and a growing global population, perhaps it makes more sense to try to cut the energy we use and reduce our dependence on cars than simply to substitute biofuels for oil and carry on as we are. Scientists are urging us to act quickly to reduce the impacts of global warming, but it might pay us to take a bit more time with biofuels and act more wisely. In our haste to protect the planet, we have to be absolutely certain we're not helping to destroy it.