Adhesives (glues)

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: June 25, 2022.

Have you ever stopped to think why glue doesn't stick to its tube? Have you ever wondered why, when you open up a jam sandwich, there's jam on both pieces of bread when you put it on only one slice to begin with? If it's ever bothered you how adhesives work, and why they fail, you're not alone. That question has taxed some of the world's best minds since ancient times. Even after all these years, scientists still don't fully understand how gluey substances make one thing stick to another, though they've got some pretty good ideas. Let's take a closer look!

Listen instead... or scroll to keep reading

Photo: Without adhesives, all kinds of everyday jobs would be much more difficult. Adhesive bandages ("sticking plasters") work a bit like sticky tape: they use a pressure-sensitive adhesive on a plastic or textile backing. Historically, bandages like this used "natural" adhesives made from rubber and rosin. Today, they're more likely to use synthetic adhesives such as acrylic resins. These adhesives have to be sticky (but not so much that they rip your skin), water resistant, and hypoallergenic (not causing an allergic reaction).

Sponsored links

Contents

Old and new glues

Photo: PVA (polyvinyl acetate) is a typical household adhesive, commonly used for sticking wood together. Here's a small sample that I squirted out, next to its container.

According to historians and archeologists, adhesives have been used for thousands of years—probably since Stone Age cave dwellers first applied bitumen (a tarry substance used to surface highways) to stick flint axeheads to the tops of their wooden hunting spears. In ancient times, people made their glues from whatever they found in the world around them—such things as sugar, fish skins, and animal products boiled in water.

Artwork: Mucilage (a sticky substance, mostly obtained from plants) is a natural glue that formed the basis of popular adhesives like Carter's Mucilage (pictured here in an 1871 product label). Courtesy of US Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

We still use some of these natural adhesives today, though we're much more likely to use artificial adhesives made in a chemical plant. It's obvious modern glues are chemical products from the horrible names they have—polyvinyl acetate (PVA), phenol formaldehyde (PH), ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), and cyanoacrylate ("super glue") to name just four. Many modern adhesives are called synthetic resins for no good reason other than that resin (a gooey substance found in pine trees and other plants) was one of the first widely used adhesives.

Artwork: Flypaper is a simple way of trapping pesky insects on adhesive-coated paper. Back in the 19th century, you could buy commercial fly paper like this "Sure Catch" (made by J. Hungerford Smith Co. of Rochester, NY, USA), but it was easy to make your own using sticky natural adhesives like molasses or bird lime (itself made from tree fruits or bark). Photo courtesy of US Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

How forces make things stick

Knowing what something is called is a far cry from knowing how it works. That was a lesson the Nobel-Prize-winning American physicist Richard Feynman (1918–1988) often used to teach. So let's forget all about adhesives, acetates, and acrylates and try to figure out why one thing will stick to another. If you want a short answer, the word is "forces."

People stick to Earth's surface even though the planet is rotating at high speed, and even there's no glue on the soles of our feet. The reason is simply that gravity bonds us to the planet with enough force to stop us whizzing off into space. But gravity isn't enough to keep us permanently in place. If we supply bigger forces, for example by using our muscles to move our legs and jump in the air, we can "unstick" ourselves and go somewhere else. Life on Earth is a bit like being a giant living Post-it® note—only with legs!

So you don't always need a blob of adhesive to stick things together. That much is blindingly obvious whenever it rains on your window. Gravity tries to pull the water down to the bottom of the glass, and sooner or later it usually wins, but two interesting things try to stop it. First, water molecules (two atoms of hydrogen and one atom of oxygen joined together) naturally stick to one another, so they clump together in big droplets on the window. The forces that make them do this are called cohesive forces (and the process involved is called cohesion). Second, the water droplets also stick to the glass without any help or glue. Different forces are at work here known as adhesive forces (the sticking process is called adhesion). Now the cohesive forces must be bigger than the adhesive forces or the water wouldn't form droplets at all. Instead, it would just spread out in a very thin layer on the glass—much as oil does when you spread it on water. But the adhesive forces are still pretty strong: some of the water droplets that stick to your window are surprisingly big.

Artwork: Cohesive forces stick water drops together, while adhesive forces stick them to your window. These two types of forces pull upward on the bottom drop, helping it to resist the downward pull of its own weight.

Next time it rains, watch how the water behaves. See how the rain naturally clumps into droplets (because of cohesion), which remain on the glass (because of adhesion). The drops fall down the window only when they're too heavy for the adhesive forces to keep them in place (when the gravitational force pulling them down is greater than the adhesive force holding them up). Notice how they run down the window in distinct tracks, with droplets following existing, watery paths. That's because the water drops that are falling are trying harder to stick to the water that's already there rather than to the glass (cohesion at work again). Why does the rain form those streaky channels? Because as drops fall down the glass, cohesive forces tear some of the water molecules away from passing drops, leaving behind droplets that are small enough to stick to the glass (adhesion again).

Adhesive and cohesive forces in glues

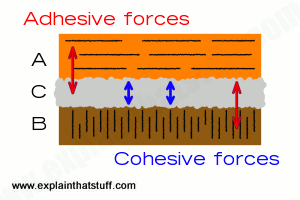

Artwork: Adhesive and cohesive forces both play a part in sticking things together.

What does all this have to do with adhesives? Adhesive and cohesive forces are also at work in glues. Let's say you want to stick together two bits of wood, A and B, with an adhesive called C. You need three different forces here: adhesive forces to hold A to C, adhesive forces to stick C to B, and cohesive forces to hold C together as well. The first two are pretty obvious: the glue has to stick to each of the materials you want to hold together. But the glue also has to stick to itself! If that's not obvious, think about sticking a training shoe to the ceiling. The glue clearly has to stick both to the training shoe and to the ceiling. But if the glue itself is weak, it doesn't matter how well it sticks to the shoe or the ceiling because it will simply break apart in the middle, leaving a layer of glue behind on both surfaces. That's a failure caused when the adhesive forces are greater than the cohesive ones and the cohesive forces aren't big enough to overcome the pull of gravity.

Jam sandwiches may not be the first thing to spring to your mind when you think about adhesives, but the jam is working as a kind of glue. It's made of sugar and water: a classic adhesive recipe used since ancient times. If you use fairly strong bread, you can pick up a jam sandwich by just one corner of one slice and the whole thing will stay together in your hand—thanks to the jammy glue. Jam has pretty high cohesive forces (that's why jam can be hard to dig out of the jar with your knife), but its adhesive forces are high too. If you butter two pieces of bread and cover one slice with jam, then close up the sandwich, then peel it apart, you'll find there's some jam left on both surfaces. As you pull apart the sandwich, you'll find the jam breaking itself in two in lots of little strands. That's because the adhesive forces are stronger than the cohesive ones. Your jam sandwich "fails" due to a failure of cohesion.

Photo: When you put spread on a single slice of bread, make a sandwich, then peel the sandwich apart, you'll find there's some spread on both slices. This ground-breaking scientific experiment demonstrates a catastrophic cohesive failure of the spread as a glue. Unlike most experiments, it also tastes good.

This illustrates another important point about glue: adhesive is a relative term. Whether something glues effectively or not depends on the size of the forces it has to hold against. You can easily "glue" a glass of water to a coaster if the bottom of the glass is wet and the coaster is light. That's because the adhesive and cohesive forces involved—holding the coaster to the glass—are greater than the coaster's own weight. But you can't use water to glue a coaster to a block of wood or a lump of metal. You can't glue yourself to the ceiling with water, though an insect might be able to manage it.

How do cohesive forces work?

Now we know that adhesives work through adhesive and cohesive forces, we need to understand a bit more about how those forces themselves work. Let's start with cohesive forces. As you can discover in our main article about the magic of water, water molecules join together with one another because they're not symmetrical. One end has a slight positive charge, the other end has a slight negative charge, and the positive and negative ends of different molecules snap together like the opposite ends of magnets. That's a kind of electrical or electrostatic bonding. In metals, the atoms are strongly held together in a rigid crystal structure called a lattice (a bit like scaffolding or a climbing frame with atoms at the joins and invisible bars holding them together). You can easily separate one "piece" of water from another (by lifting some out with a spoon): the cohesive forces are quite weak. But you can't easily separate one bit of iron from another (with a spoon or anything else) because the cohesive forces are incredibly strong.

Water and iron are both pretty useless as glues, but for quite different reasons. Water could be an excellent glue because it sticks quite well to other substances (such as glass), but its cohesive forces are incredibly weak. You can stick paper to the wall by wetting it first, but you can usually peel it off quite easily too. When you peel, you're breaking the weak cohesive forces that hold one water molecule to another. Iron is no good as a glue because it's too preoccupied with sticking to itself to stick to anything else. All its forces are occupied internally, fixing one iron atom to another in a strong cohesive structure. There's nothing it can use to attach itself to other objects: its adhesive forces are virtually nonexistent.

Photo: Sticky tape (also called Scotch® tape and Sellotape® after two well-known brands) is simply a pressure-sensitive adhesive on a convenient, transparent, film backing.

Sponsored links

How do adhesive forces work?

Now for the real question: what makes a gluey substance stick to something else? You may be surprised to hear that there's no single, simple answer—but that's not so surprising if you consider how many different types of glue there are and how many different ways in which we can use them. For each different glue, and each different surface we use it on, scientists think a combination of different factors are at work holding the two together. But the plain truth is: no-one exactly what's going on in every case.

Artwork: Four theories of how things can stick. Clockwise from top left: 1) Adsorption is a surface sticking effect caused by small, attractive forces between the adhesive (yellow) and the substances it's sticking (red and blue). 2) Chemisorption involves chemical bonds forming between the adhesive (orange) and the substances it's sticking together. 3) Diffusion sticks two things together when molecules cross the boundaries from one into the other and vice-versa. 4) Mechanical adhesion happens when a glue (green) fills the space between two substances and the cracks inside them, creating a strong physical bond.

One of the main factors is called adsorption. When you spread adhesive, it wets the surface you apply it to. Lots of very weak electrostatic forces between the glue molecules and the molecules in the surface (called van der Waals forces for the physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals (1837–1923) who discovered them) hold the two things together. For adhesives to work well like this, they have to spread thinly and wet the surfaces very well. There's no actual chemical bond between the glue and the surface it's sticking to, just a huge number of tiny attractive forces. The glue molecules stick to the surface molecules like millions of microscopic magnets.

In some cases, adhesives can make much stronger chemical bonds with the materials they touch. For example, if you use certain glues on certain plastics, the glue and the plastic actually merge together to form a very strong chemical bond—they effectively form a new chemical compound at the join. That process is called chemisorption.

Adsorption and chemisorption are chemical connections between the glue and the surface. Glues can also form physical (mechanical) bonds with the surface they're sticking to. Suppose the surface is porous (full of holes). The glue can seep into those holes and grip through them, like a climber's fingers grabbing holes in a rock face. That's called the mechanical theory of adhesives.

Another theory of how glues work suggests the adhesive can diffuse into the surface and vice-versa, with molecules swapping over at the join and mingling together. This is called the diffusion theory.

How do Post-it® notes work?

So what about that little Post-it® note stuck to your wall? How does that work?

Look at the back of a sticky note using an electron microscope and you'll see not a continuous film of adhesive but lots of microscopic glue bubbles, known as microcapsules, which are about 10–100 times bigger and much weaker than the glue particles you'd find lazing around on normal sticky tape. When you push a Post-it® onto a table, some of these relatively large sticky capsules cling to the surface, providing just enough adhesive force to hold the weight of the paper in the little note. Every time you attach and peel off the note, dust and dirt attach to the adhesive capsules, so they progressively lose their stickiness. But since there are so many capsules of all different sizes, a Post-it® note does go on sticking for quite a while.

Photo: Post-it® notes attach themselves with help from lots of "microcapsules" (tiny microscopic bubbles of adhesive) on the reverse, which are much larger than the glue particles on conventional sticky tape.

Sponsored links

Why doesn't glue stick to the tube?

Photo: Epoxy glues are made of two substances that become sticky only when you mix them. Often they're packaged in a pair of syringes joined together, like this.

Adhesives are designed to work when they leave the tube—and not before. Different adhesives achieve this in different ways. Some are dissolved in chemicals called solvents that keep them stable and non-sticky in the tube. When you squeeze them out, the solvents quickly evaporate in the air or get absorbed by the surfaces you're sticking to, freeing the adhesives themselves to do their job. Plastic modeling glue works like this. It contains molecules of polystyrene in an acetone solvent. When you squeeze the tube, the glue spurts out and you can usually smell the very strong acetone as it evaporates. Once it's gone, the polystyrene molecules lock together to make strong chemical bonds. Glue doesn't smell when it's dry because all the solvent has vanished into the air. Some glues (such as synthetic, epoxy resins) have to be mixed together before they work. They come in two different tubes, one containing the synthetic resin and the other containing a chemical that makes the resin harden. The two chemicals are useless by themselves but, mixed together, form a tough, permanent adhesive.

Photo: 1) Stick adhesives are solvent-free and

very safe to use. 2) Spray-on adhesives often contain harmful solvents and it's a

good idea to wear a safety mask or use them outdoors.