Environmentalism

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: October 13, 2022.

You probably take pretty good care of the place you live in: you clean it, you keep it warm, you carry out repairs when they need doing, you tidy the garden, you're nice to your neighbors and help them when you can—generally speaking, you look after your home and its environment because your home looks after you. Our planet, Earth, is just as much our home, but we don't look after it anything like as well. We use its resources, we pollute it with trash, we plunder from our neighbors (other animals and plants) without a care, and we give little or no thought to what things will be like in the future, never mind what shape things will be in for our children.

Environmentalism is a different way of thinking in which people try to care more about the planet and the long-term survival of life on Earth. It means recognizing the planet's environmental problems and coming up with solutions (individually and collectively) that try to put them right.

Photo: Earth from space—magical, isolated, and fragile. When astronauts showed us scenes like this, they paved the way for the modern environmental movement. Picture by courtesy of NASA on the Commons.

Sponsored links

Contents

What problems does our planet face?

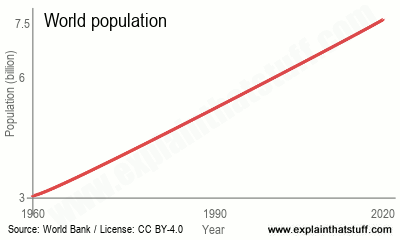

Earth can seem an enormous place—it's a giant ball almost 13,000km (8000 miles) in diameter. Walking constantly at a steady speed, it would take you at least a couple of years to go in a complete circle from where you are now, right around the globe, back to your starting point (assuming it were physically possible). When you live somewhere as big as this, it's easy not to worry too much about the state of the environment; after all, there's always plenty more environment where that came from, right? Wrong! There are almost 8 billion people living on planet Earth, consuming resources, making pollution, and using so much energy in such an inefficient way that we're fundamentally changing how the climate works, risking life in the future for hundreds of millions of people. Here are just a few of the problems the environment is now facing...

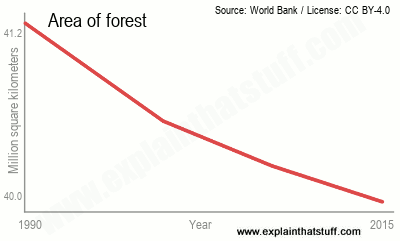

Please note: The charts on this page are greatly simplified to show the overall trend in different aspects of our planet's environmental health (such as energy use, population, and so on). Typically, they show just two points, one a few decades in the past and one more recent, with a line between to indicate the overall trend. The vertical axis usually does not start at zero. Presented this way, the charts may look exaggerated, but they are meant to simplify rather than deceive.

Resources

We live by consuming—buying things and throwing them away, sometimes without even using them. Elsewhere on the planet, millions of people live in dire poverty with too little food, no proper water supply or sanitation, and horrible health problems. Earth is a finite place with limited resources, yet we live as though our supply of raw materials will never end. Modern humans have successfully lived on planet Earth for something like 200,000 years, but some of the materials we now critically depend on—metals, minerals, and so on—will last only a few more decades and many more will be gone in a few hundred years, at best. We've become very short-sighted all of a sudden!

Chart: Growing population is one of the greatest pressures on the planet. Please note that the vertical axis of this chart does not start at zero. Drawn using data from World Bank DataBank, published under a Creative Commons CC BY-4.0 Licence.

Energy supply

A basic law of physics (the conservation of energy) tells us it's impossible to do anything on earth without using energy—even something as simple and effortless as thinking needs us to consume food, which is simply energy we feed in through our mouths. Our homes need energy too, for cooking, heating, making hot water, and running all the appliances and gadgets that make our lives comfortable.

Though a small amount of our energy is renewable (things like solar power, wind power, and tidal power will theoretically never run out), most comes from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. The planetary "fossil-fuel tank" inside Earth took hundreds of millions of years to fill up, but humans have emptied the vast majority of it in just the couple of hundred years or so since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. How are we going to meet our energy needs in future when most of the fossil fuels have gone, especially with more people living on the planet (and in greater affluence) than ever before?

Chart: Developed countries such as the United States and UK use energy much more efficiently than they use to. However, growing energy use in the developing world means overall energy use per person is still increasing dramatically for the world as a whole. Please note that the vertical axis of this chart does not start at zero. Drawn in 2022 using the latest available (2014) data courtesy of OECD/IEA and World Bank DataBank.

Waste and pollution

There's almost nothing we do that doesn't create some form of waste as a byproduct. Before the 20th century, that wasn't really a problem: people were pretty good at turning things like food or animal waste into compost—they certainly didn't have things like landfill sites and incinerators. These days things are very different because we use a far greater variety of materials, including plastics, which are harder to recycle or dispose of. Even though most plastics are made from petroleum (a finite and relatively scarce material), still we tend to throw them away rather than recycle them. Waste is one thing: if we can contain it and collect it, at least we can recycle it or dispose of it responsibly. Sometimes, though, waste becomes pollution: solids, liquids, or gases we throw out into the environment without caring where they end up or what damage they do.

Some of the gases we hurl into the air stay in the atmosphere, trapping heat around our planet like a blanket. This is known as the "greenhouse effect" and it's giving rise to probably the biggest environmental challenge of all, climate change, which could have a devastating effect on many of our planet's lifeforms in the coming decades and centuries.

Chart: There's a widely recognized need to tackle climate change. Even so, the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions causing it continue to climb. Drawn using data from Climate Watch, 2020 courtesy of World Resources Institute and World Bank DataBank, with original data published under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC 4.0) Licence.

Habitats and species

Chart: Deforestation (the loss of forest cover to agriculture and urban spaces) continues to be a major issue. Between 1990 and 2015, the total forest area fell from 41.2 million square kilometers to 39.9 million square kilometers. Please note that the vertical axis of this chart does not start at zero. Drawn using data from World Bank DataBank, published under a Creative Commons CC BY-4.0 Licence.

Humans have become dominant on Earth through the luck of evolution, but we tend to regard ourselves as though we are the only species on the planet—and certainly the only one that matters. With the exception of the pets we keep for amusement, we give little or no thought to other species—plants or animals—or their habitats (the places where they're most suited to living). We happily build homes, factories, and highways for ourselves by obliterating the homes of other species. Mostly we consider animals have no rights at all, though contrary views don't trouble us much: we abhor cruelty and sometimes oppose things like laboratory experimentation on animals, but we turn a blind eye to the billions of creatures raised in appalling conditions and slaughtered in food factories to put cheap, convenient meals on our tables.

Map: Huge numbers of plant and animal species are currently at risk. This map shows the number of threatened bird species in each region. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has noted a steady, ongoing decline in the world's birds since it carried out the first complete assessment in 1988. Source: United Nations Environmental Program and the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, and International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List of Threatened Species, published by World Bank DataBank under a Creative Commons CC BY-4.0 Licence.

Sponsored links

Social justice

Some environmental problems are caused not just by the way humans relate to the natural world, and to animals, but to the way we treat one another. People in the rich countries of Europe and North America often frown on people in developing countries who burn rainforests, have large numbers of children, or live in grossly polluted cities. We conveniently ignore the fact that poorer people are often condemned to live that way by the unfair rules of international trade. If we pay people in developing countries a pittance for products like coffee, cotton, or rubber, is it any surprise that they have larger families to try to generate more income to help themselves survive? If we don't share our medicines with them so their children die, isn't it natural that they should have more children to compensate? Politicians like to applaud themselves on how much waste people are now recycling and how much fuss is being made about cutting the greenhouse gases that cause global warming—but we're doing those things partly by exporting our problems to developing countries: we quietly ship our toxic waste to Africa and much of the stuff we buy is manufactured in countries such as China, so we've effectively exported our greenhouse emissions and pollution overseas. We're very good at brushing environmental problems under someone else's carpet.

Photo: Problems like pollution and climate change, which we might consider purely "environmental," are linked to much wider and more complex social issues. Photo by Vicki Francis/UK Department for International Development, published on Flickr under a Creative Commons Licence under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

What are the solutions?

Recognizing a problem is always the first step in finding a solution. Environmental concepts such as "ecosystems," "sustainable development," "biodiversity," and "peak oil" are examples of how we can understand the fragility of our environment, frame our environmental problems, and try to find solutions. The solutions we actually come up with are a mixture of different approaches involving conservation, law, economics, technology, education, social justice, personal change, and activism. Let's look at these in turn.

Conservation

Long before it was fashionable to discuss the environment, people talked about "conservation": direct preservation of birds, wilderness areas, national parks, open spaces, and so on. Most of the older environmental groups, including the National Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, and (more recently) the World Wildlife Fund, came into being as conservation bodies. Newer groups such as Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Friends of the Earth (FoE) have tended to take a broader view of a whole range of environmental issues; the older conservation groups have also reoriented themselves to take account of the fact that habitats and species are often threatened indirectly by such things as global warming or energy policy. All the same, preserving wilderness for its own sake remains an important part of environmental protection, informed by concepts such as the ecosystem (the idea that many species depend on one another for survival) and biodiversity (Earth's dazzling range of different species, and the habitats that support them).

Laws

If something people do harms the environment, why not simply make it illegal? Laws and other regulations have become an important means of solving environmental problems over the last few decades. We now have laws to protect species, prevent pollution, mandate recycling, ban the use of harmful chemicals, and much more besides. Since environmental problems are often international or global, international laws and agreements have a large part to play as well. In Europe, for example, the member states of the European Union are bound by collective environmental laws (known as directives) as well as their own national laws—and the international laws take precedence. There have been some notable successes, including the London Dumping Convention (LDC) to prevent dumping of waste at sea and the Montreal Protocol (an agreement to ban chemicals that harm Earth's ozone layer). But attempts to reach global agreements on climate change have so far been disappointing and ineffective.

Economics

Like it or not, money makes our world go round. One reason the environment is often degraded or destroyed is that parts of it have little or no financial value. If a new highway is planned, it's usually cheaper to route it through a park or wilderness area (which has no value, because no-one could build homes there) than through urban wasteland (because that has a market value); in other words, there's often an economic incentive to destroy rather than preserve the natural world. In much the same way, it can make sense for a farmer in a developing country to burn down rainforest to grow a cash crop such as coffee, even though the forest may be home to a dazzling diversity of important species. One solution is to put prices on harmful activities. In the UK, for example, local governments who want to bury waste in the ground have to pay so much landfill tax per tonne and that gives them an incentive to recycle more. Making people pay if they harm the environment is sometimes called the polluter pays principle.

Technology

Photo: Should we put our faith in technologies like solar power to solve our environmental problems?

History suggests we can often find innovative, scientific solutions to the problems we encounter as civilization progresses. For example, agricultural machinery, pesticides, and fertilizers have made it possible to produce vastly more food from the same amount of land with a much smaller workforce. People with great faith in technology believe we will be able to pull off similar miracles in future—perhaps stopping global warming by fundamentally altering Earth's climate through technological fixes known as geoengineering. Then again, many people are deeply suspicious of technology and fear that it causes more problems than it solves. Nuclear power, for example, was originally billed as a virtually free, everlasting source of energy, but it was developed at enormous expense, and with huge amounts of highly toxic nuclear waste as a byproduct, largely so the world's superpowers could develop nuclear weapons at the same time.

Education

One reason people harm the environment is that they simply know no better. How would you ever know that polar bears in the Arctic are being polluted with PCBs (chemicals we've used to manufacture electronic equipment in countries such as the United States) unless you'd read about it in something like National Geographic or seen it on TV? Thankfully, our scientific understanding of the environment is improving all the time. And thanks to brilliant new tools like the World Wide Web, it's much easier for people to learn about environmental problems and share their concerns than ever before. Environmental topics are taught much more widely than they were 20 or 30 years ago, so future generations will hopefully have a much better awareness of the need to protect the planet.

Understanding the links between poverty, trade, people, and the planet that supports them is a hugely important and often neglected part of environmentalism. Initiatives such as fair trade (which means paying producers more money for commodity goods like coffee and cotton) can be a start in helping to reduce poverty. And when people aren't struggling to survive, they can devote more attention to healthcare, education, and protecting their environment. There's little chance of protecting the planet unless we understand how and why people feel they need to destroy it.

Chart: Looking up: It's not all bad news! The number of people living in slums continues to decline in most countries. The percentage of the urban population who are slum dwellers fell from almost half in 1990 to about 29 percent in 2014. Please note that the vertical axis of this chart does not start at zero. Drawn using data from World Bank DataBank, published under a Creative Commons CC BY-4.0 Licence.

Personal change

A central part of environmentalism is recognizing the damage you inflict on the planet yourself and doing what you can to minimize it. That means buying things more wisely (choosing organic food that doesn't pollute the soil, for example); reducing, reusing, and recycling things before you buy new ones; using public transportation instead of cars and taking trains instead of planes; insulating your home; and opting for renewable energy over fossil fuels. Environmentalists sometimes invite ridicule by taking measures like these to extremes; and the idea that "every little helps" the planet is sometimes a cruel delusion: installing a hopelessly inefficient, rooftop, micro-wind turbine that consumes more electricity than it produces is an example of how our desperation to do the right thing can lead us astray. Generally, though, "going green"—making fundamental personal changes to reduce your impact on the planet— is what environmentalism is all about.

Photo: An organically grown cabbage looks (and maybe tastes) no different, but it's better for the environment because it's been grown without adding artificial pesticides and chemical fertilizers to the soil. Organic has other benefits too: organic growers have generally higher environmental standards and better standards of animal welfare.

Activism

Even if you could revolutionize your life to the point where you had zero impact on the planet, you'd make absolutely no difference to problems such as pollution and climate change unless you could persuade lots more people to do the same. That's why many environmentalists ultimately become activists: people who campaign for wider change in society.

Eco-activists come in many different flavors—and strengths. Some are content to pay a subscription to green groups and let them do the campaigning on their behalf, while others form green parties to put environmental issues on the political agenda. Some activists reject conventional politics altogether, preferring to confront environmental threats head-on with direct action (for example, locking themselves to bulldozers or chaining themselves to railroad tracks to stop nuclear waste shipments). Others connect environmentalism to broader social and political ideas. Eco-feminists, for example, trace many of Earth's problems to our male-dominated society, likening the plunder of planet to the historic domination of women by men. Deep ecologists reject shallow, feel-good environmentalism in favor of a much more philosophical and spiritual approach to our human-obsessed (anthropocentric) view of the world and issues like the preservation of wilderness for its own sake. Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the spectrum, green capitalists believe our existing economic systems can be tweaked slightly so companies can continue to make profit while protecting the environment, and politicians talk of "sustainable development" (a suspiciously hard-to-define phrase that often boils down to muddling along, business as usual, and hoping things turn out alright in the end).