Do people care enough to save the planet?

by

On the M25 orbital motorway around London, motorists spend the equivalent of 29 years at a crawl on a typical day [1]. Many of the cars have tiny stickers in the back window, WWF pandas, RSPB birds, exhortations to "Save the whale" or (quite a rarity these days) terribly British declinations of another Chernobyl: "Nuclear power, no thanks". There is no shortage of pro-environment display even amid such anti-environment behavior. Contrary attitudes are far from uncommon. In 1970, 80 per cent of seven and eight year olds traveled to school by themselves; now, the figure is down to a tiny 9 per cent, and parents cite fear of traffic as the main reason [2]. School runs account for up to 30 per cent of peak hour traffic in central London. Just as dogs chase their tails, so parents, it seems, chase their exhaust pipes.

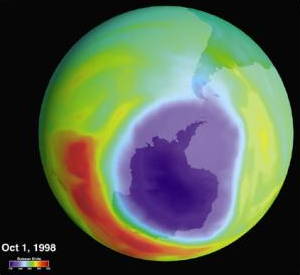

Photo: The huge hole in Earth's protective ozone layer over Antarctica, shown here in a satellite photo taken in 1998. In what was widely seen as a triumph for

Ambivalent about the environment?

"Why are so many millions of people who are apparently concerned about the environment

unwilling to reflect this in their own lifestyle?"Jonathon Porritt

A number of attitude surveys have confirmed that ordinary people (by which I mean people who are not green activists) are extraordinarily ambivalent when it comes to the environment [26]. Mainstream politicians often cite this as the reason for slow progress on environmental change, which can certainly be very convenient. Is it not possible that corporations and interest groups with an agenda contrary to environmentalism exploit public confusion and ambivalence to ensure nothing ever does change? Is it possible that these groups might go even further and use the confusion to rollback existing legislation and policies that aim towards environmental protection? Andrew Rowell's book Green Backlash suggests that both of these things are more than possible [16].

So what produces such ambivalent attitudes to the environment. How can people believe apparently contradictory things at the same time? Do the greens actually contribute to the ambivalence and confusion, as John Gummer suggests, by "selling the environment wrongly"? [9] Is it possible to move through this confusion and ambivalence towards a clear public understanding of environmental concerns and a real process of change? Is that realistic or possible, or just hopelessly naïve?

The big question is not whether we are making progress in halting environmental degradation, for we certainly are, but whether we are making genuine progress, and making it quickly enough to offset—and reverse—the rate at which we are doing damage. The problem is not the importance of green issues, but ordinary people's understanding of those issues. Few can doubt that the problems have ever been more pressing, or that the greens have ever been more active... but is the message getting across where it counts?

Green activists and professional campaigners rarely seem to ask this rather obvious question; the self-analysis and honesty that should be central to all green campaigns is left, by default, to newspaper commentators on the sidelines. In 1997, a leader in The Independent suggested: "The public's green consciousness is unformed, full of confusions about the relative importance of different environmental issues. This is not helped by what appears to many people as tree-hugging mysticism, obscuring the link between road-building and climate change, for example." [7] The Guardian's Hugo Young offers a variation: "The green cause is as much about teaching and converting as campaigning and winning... public awareness is the name of the game. Who can most seriously raise it, striking a chord among people ready to be persuaded that things have got to change?" [12]

The way we live now

Is there widespread apathy about the environment? Is it simply an issue about which people couldn't care less? Apparently not. Somewhere between three and five million people in the UK (the ambiguity in the figure is explained later) belong to environmental pressure groups such as Greenpeace, Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE), and Friends of the Earth (FoE). Direct action protests against environmental myopia (Twyford Down, the Newbury bypass, the Brent Spar, German anti-nuclear protests) have regularly made international news. There can be little doubt that the environment concerns most people, to a greater or lesser degree; but what it does not yet do, is concern them enough to move them towards decisive and consistent action. Public opinion on environmental issues is best characterized as "ambivalent".

In an earlier article about environmental activism, I contrasted the rather amateur evangelical approach of green activists with the slick kind of approach that might be taken to this problem by marketing professionals, suggesting green campaigners need to start from where ordinary people are and what they are prepared to listen to, rather than from what activists themselves are desperate to say. The first step towards that approach is understanding, either anecdotally (qualitatively) or scientifically (quantitatively), what people really think about the environment and what they're prepared to do and pay to protect it.

What people really think about the environment

Reliable data about public attitudes to environmental issues is surprisingly hard to come by. Typically, polls ask questions in isolation, failing to assess the relative importance of green concerns to other matters of social and economic importance. Or they ask one-off opinions straight after environmental disasters, or when public concern is artificially and temporarily stimulated by some sudden change or stress. Surveys such as the annual Social Trends typically document the changes in behavior over a number of years, rather than attitudes or opinions, or why people think they behave the way they do (or, even more to the point, why they actually do behave that way).

A notable exception to this was the survey carried out by the Department of the Environment (DoE) in 1989, published in 1992, presumably in the wake of government concern that the environment had suddenly become a "real" issue. In the 1989 European elections, the Green Party polled 14.5 per cent of the vote, obliging even Mrs "Not for turning" Thatcher to reassess her view of the environment; it was no longer "humdrum", but suddenly "one of the great challenges of the late twentieth century" [3]. There was a great deal of green talk at the time. Preparations were well underway for the Earth Summit due to be held at Rio in 1992. Aerosols and ozone holes had become a source of great public concern. Climate change was forcing its way to the top of the political agenda. Perhaps as a response to this, 1992 saw the publication of the comprehensive Department of the Environment survey of The UK Environment [4]. Unusually, it contained not merely a comprehensive assessment of the state of Britain's environment, but a whole chapter on "Public Attitudes", measured in 1989. The results can be divided into a number of different areas:

1. How important is the environment compared to other issues?

In July 1989, 35 per cent of people questioned in the DoE survey said that the environment is "one of the most important problems the government should deal with", up from 6 per cent in 1986. In this poll, the environment came second only to the NHS and social services, scoring higher than unemployment (the biggest issue in 1986), crime, housing, and education.

2. What issues concern people at different geographic levels?

Locally, people were most concerned about fouling by dogs and litter. Retired people, most likely to be concerned with their immediate local environment, were not surprisingly most concerned about these issues.

Nationally, people were asked to select "the most important problem in Britain". Radioactive waste was chosen by 56 per cent of respondents in a 1986 survey (perhaps a confused and emotive response to the Chernobyl explosion on 26th April of that year). In 1989, 18 per cent of people chose radioactive waste, 10 per cent chose chemical pollution of rivers and seas, 10 per cent chose destruction of the ozone layer, 9 per cent chose inner city decay; and 8 per cent chose sewage on beaches and in bathing water.

On a global level, the four most serious problems identified were the ozone layer (22 per cent), radioactive waste (20 per cent), destruction of the rainforests (17 per cent), and global warming (14 per cent). In 1995, the British Social Attitudes Survey found that 60 per cent of people believed that global warming would 'definitely' or 'probably' be one of the most serious problems in the future [5].

3. Can we solve our problems? Who should solve them?

"In the 1989 DoE survey, at least half felt 'quite a lot could be done about' all the problems listed. Over 90 per cent thought that quite a lot could be done about chemicals put into rivers and the sea, and sewage contamination of beaches and bathing water. Those problems where more people thought some action could be taken, were also those causing most concern." [4]

People must have been feeling overwhelmingly positive at the time of the survey, for more than 60 per cent felt "a lot could be done to resolve" river and sea pollution, sewage in seas and on beaches, drinking water quality, use of pesticides, the ozone layer problem, use of derelict land, nuclear waste, factory fumes, acid rain, and global warming.

Having identified that so much potentially could be done to sort out our environmental problems, who did people feel should be doing it?

The majority of respondents allocated responsibility mainly according to the geographical extent of the problem; for example, 57 per cent thought that local councils should be doing something about litter and rubbish and 71 per cent thought that international bodies should be doing something about the destruction of the rainforest... For two thirds of the problems listed, the majority of respondents thought that the British Government was responsible for making sure something was done." [4]

4. What are you willing to do? How much are you willing to pay to protect the environment?

Asked about what sorts of action they would be willing to take to protect the environment, roughly 60-80 per cent of the people questioned were either doing, or would consider doing, all the things listed in the survey—from using ozone-friendly aerosols to avoiding garden pesticides, and from using unleaded petrol to buying phosphate-free washing powder. A follow-up survey in 1981 confirmed this high level of concern:

"The most common action was buying ozone friendly aerosols (or buying no aerosols) and three quarters of respondents had done this. Next most common actions were cutting down on the use of electricity (65 per cent), buying products sold in recycled packaging (56 per cent), buying products made from recycled materials (53 per cent), and regular use of a bottle bank (45 per cent). Generally, people appear to concentrate on a few issues where simple and clear action is possible." [4]

Green consumerism—the trend for buying products that claim to be

better for the environment—apparently continued at a high level, at

least until 1992, with around 40 per cent of people regularly selecting

"one product over another because of its environment-friendly

packaging, formulation or advertising in the last year or two" [4]. But

despite continuing high levels of environmental concern, the number of

people who have stuck to their green guns in recent years has been low,

as statistician Sharon Witherspoon points out: "Fewer than one per cent

of consumers behave in a consistently environmentally-friendly way."

[26] There can be no question that ethical consumerism reflects a

genuine concern for the environment, especially as these products are

rarely stocked in shops, hard to find when they are stocked, and

usually more expensive than alternatives. Given the

There is never any shortage of commitment in principle to protecting the environment; many people say they are even willing to sacrifice economic growth to that end (figure 1).

Fig 1: Attitudes to the "trade-off" between protection of the environment and economic growth, 1982-1988

| Percentage of respondents selecting their priority | Oct 1982 | May 1985 | Sept 1986 | Oct/Nov 1988 |

| Priority should be given to... | ||||

| The environment (1) |

50 |

57 |

54 |

70 |

| Economic growth (2) |

36 |

32 |

29 |

17 |

| Neither/don’t know |

14 |

11 |

17 |

12 |

Notes:

- "Protection of the environment should be given priority, even at the risk of holding back economic growth."

- "Economic growth should be given priority, even if the environment suffers to some extent."

By September 1988, nearly three quarters of people in Britain were willing to give priority to the environment, even at the expense of holding back growth. Further questioning suggested an even more enlightened attitude; in three surveys between 1986 and 1989, approximately 50 per cent of people agreed that "Protecting the environment and preserving natural resources are necessary conditions to ensure economic development", with around 30-40 per cent of people agreeing "Sometimes it is necessary to make a judgment between economic development and protection of the environment", and only 9 per cent opting to give automatic priority to economic growth.

Sharon Witherspoon quotes similar enthusiasm in a 1993 survey of the British people, in which only 38 per cent of people questioned agreed with the statement: "We worry too much about the future of the environment and not enough about prices and jobs today" [26]. But given that recent British governments have been elected by not much more than 38 per cent of the people, this is not a decisive victory for green thinking.

The reservations about economic growth are not merely British. Lunch and Rothman (1995) have investigated what trade-offs Americans are prepared to make between having adequate energy and protecting the environment. In times of energy crisis, people naturally favor adequate energy "even though it means taking some risks with the environment"; at other times, protecting the environment is rated more highly. In one survey they quote, almost two thirds of people questioned chose to "have both" [8].

These questions still don't test people absolutely—economic growth is still some way removed from the pound in our pocket. What, exactly, do people feel about their own individual responsibility and how much would they be prepared to pay directly to safeguard the environment? The DoE noted a problem:

"Various surveys have attempted to address the question of whether people would be willing to pay for environmental improvements, either through higher prices for environment-friendly goods, or through higher taxes to fund government spending on environmental protection. However, the results of this kind of question have to be treated with considerable caution, since what people say and what they actually do in practice may be quite different. This means that it is not possible to identify 'willingness to pay' from general surveys. For example, in the 1989 DoE survey, 71 per cent of respondents said that they thought it was 'a good idea' to increase the price of petrol by 17 pence per gallon so that less harm was done to the air, but it was not until the Government reduced the duty unleaded petrol to make it cheaper than leaded, that a significant proportion of customers began to buy unleaded fuel." [4]

And the year-on-year increases in fuel have since created considerable resentment amongst haulage contractors and lorry drivers.

Only 2 per cent of people in the 1989 DoE survey felt the country could not afford to spend anything on environmental protection. 35 per cent favored cuts in other areas of public spending; those in higher income groups tended to favor higher taxes. About 30 per cent of people questioned felt the environment could be protected if industry charged higher prices for polluting goods at the point of purchase.

A 1991 survey in Scotland attempted to find out general attitudes to payment and responsibility. It found about 80 per cent agreement with the proposition that "It's up to individuals to protect the environment by changing their own behavior", with slightly fewer agreeing that "The Government could do a lot more than it is now to protect the environment". About two thirds of people thought environmental protection should be paid for by higher-priced products, and half favored higher taxes:

In general, the degree to which people were environmentally aware or 'green' in their everyday actions determined their attitudes towards payment and responsibility. People who were better informed about the environment supported in particular, controlling industry, paying more for environment-friendly products and paying higher taxes to protect the environment." [4]

These are impressive results—they show a high

commitment to environmental protection in principle, and a certain

determination to tackle the problems in practice. But there is a catch.

The results apply to the "freak year" of 1989 when the environment

suddenly became a big issue. Public "greenery" has advanced little

since then, as MORI's surveys on environmental action confirm (figure

2).

Fig 2: Environmental action (1) (Great Britain): Percentages.

| Year |

1988 |

1991 |

1993 |

1996 |

| Given money to or raised money for environmental

issues (2) |

28 |

27 |

54 |

51 |

| Used unleaded petrol in car |

.. |

35 |

42 |

51 |

| Selected one product over another because of its

environmentally friendly pack, formulation or advertising |

19 |

49 |

44 |

36 |

| Requested information from an organization

dealing with environmental issues (3) |

7 |

15 |

13 |

16 |

| Subscribed to a magazine dealing with

environmental issues |

8 |

15 |

13 |

14 |

| Been a member of an environmental group or

charity (even if joined more than two years ago) |

6 |

13 |

12 |

10 |

Notes:

1. Respondents were asked: “Which, if any, of the following have you

done in the last year or two?”

2. Wildlife, conservation or Third World charities.

3. Wildlife, conservation, natural resources, or Third World.

Source: Business and the Environment Survey, MORI.

This shows very clearly that, while there were great gains in green behavior from 1988 to 1991, most indicators have stayed the same or fallen back since then: comparing 1996 to 1991, fewer people give or raise money for environmental causes, buy environmentally friendly products, or belong to environmental organizations [5].

In terms of green activism, Witherspoon quotes a more recent survey finding that, in the past five years, 36 per cent have signed a petition, 29 per cent have given money, 6 per cent have been members of a group or campaign, and only 3 per cent have been on a demonstration [26].

The green pressure groups

Studying membership trends of some environment and countryside protection organizations offers a certain amount of insight into public perception (figure 3). Note particularly the massive increases from 1981 to 1991, and the relatively modest increases (or actual declines in membership) after that. Some of this might be attributable to the mid 1980s economic recession; more recent figures might show declines due to the National Lottery. But surely, if people were that concerned about the environment, they could still find ten or twenty pounds a year for RSPB or Friends of the Earth, even in a recession, and even with the lottery?

One vital piece of information these figures don't reveal is the number of people who belong to several different environmental organizations. There is a high probability of this, both because of the likelihood of appealing to the same audience, and because charities usually sell their mailing and donor lists on to one another. While this may be a good way of recruiting members in the short term, it may backfire in the longer term when people feel they can no longer support four or five environmental charities campaigning on similar issues. So although there are five million members of green organizations, far fewer than five million people actually belong to them. It's difficult to assess the total membership of these organizations, but it must lie somewhere between two and a quarter million (the membership of the National Trust) and the five million normally quoted; over 60 per cent of these are accounted for by the National Trust and RSPB alone—the two biggest groups who offer incentives to their members (access to stately homes and gardens, on one hand, and bird sanctuaries and nature reserves, on the other). And while green groups often boast that their combined membership exceeds that of political parties, we must be careful, for no sensible person belongs to more than one political party (and a lot of sensible people don't belong to any).

Fig 3: Membership of selected voluntary organizations

United Kingdom (Thousands)

|

Organization |

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

1994 |

|

National Trust |

278 |

1046 |

2152 |

2219 |

|

RSPB |

98 |

441 |

852 |

870 |

|

Greenpeace |

... |

30 |

408 |

300 |

|

Wildlife Trusts |

64 |

142 |

233 |

263 |

|

National Trust for Scotland |

37 |

110 |

234 |

235 |

|

Civic Trust |

214 |

... |

222 |

222 |

|

WWF |

12 |

60 |

227 |

187 |

|

Woodland Trust |

... |

20 |

150 |

170 |

|

Friends of the Earth |

1 |

18 |

111 |

112 |

|

Ramblers Association |

22 |

37 |

87 |

100 |

|

CPRE |

21 |

29 |

45 |

46 |

|

BTCV |

1 |

... |

9 |

10 |

|

British Trust for Ornithology |

5 |

7 |

9 |

9 |

The figures make interesting reading, especially case by case. The broad trend is for an almost tenfold increase in membership between 1971 and 1991.

National Trust: Even with a million members in 1981, the National Trust still managed to find another million in the following ten years—an impressive achievement, given that it probably could not have found these extra people amongst the members of other "green" organizations. We should remember, however, that the National Trust recruits couples, and counts them as such.

RSPB has shown a steady increase in membership, and a doubling since 1981. In advertising terms, it has a "unique selling proposition": it maintains a distinct focus on the protection of bird species and habitats and provides its members with access to RSPB-maintained bird reserves.

Greenpeace grew its supporters by a factor of almost fourteen between 1981 and 1991, but three years later had lost a quarter of them. This might reflect its controversial campaigning style, but is probably more of a reflection of the fact that it has "supporters" rather than "members", and makes appeals on specific campaigns, rather than publishing a regularly newsletter and soliciting annual contributions; it is therefore more likely to be subject to economic trends.

WWF showed strong growth from 1981 to 1991, but has also lost ground up to 1994; unlike RSPB, say, it campaigns more generally and has no unique campaign focus. Indeed, it has become even more general by changing its name from "World Wildlife Fund" to "World Wide Fund for Nature" (presumably a reflection of the need to campaign for ecosystems as a whole, for habitats as well as animal species).

Friends of the Earth managed to increase its membership around six-fold between 1981 and 1991—less than half of the rate of growth of its obvious "competitor", Greenpeace. But unlike Greenpeace, FoE has managed to retain most of its supporters. Its growth seems stronger and steadier. This is probably a reflection of its emphasis on encouraging members to campaign through strong local groups, building a long and productive relationship with the central organization. FoE has also been markedly more cautious than Greenpeace in taking risks with public opinion; its founder, David Brower, left when he found the group becoming too conservative in the 1970s [7].

CPRE: Of all the organizations listed here, the Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE) is perhaps the most surprising. In 1981, its membership was roughly comparable to that of Greenpeace. In 1994, Greenpeace had over six times more supporters than CPRE, which is known to have an ever ageing membership and difficulty in attracting younger members. CPRE is much less appealing to supporters of the environment than Greenpeace or Friends of the Earth. Whether this says something about its public perception—a blue-rinse approach, close ties with the country landowning style of conservation, and a polite respect for parliamentary process, public inquiries, and county committees—or its failure to cash in on the new environmentalism, is hard to say. Founded in 1926, CPRE is certainly old-established and traditional; but RSPB was founded in 1899 and has managed both to move with the times and grow its membership roughly nine-fold in the last twenty years.

We should be careful about reading too much into these membership figures, for there is another plausible interpretation. Many of the new breed of green activists—and particularly direct activists—don't belong to any of the green pressure groups; why should they, when each one of them is a one-person pressure group in their own right? Equally, many new green pressure groups have sprung up to fight very specific environmental threats (for example, Surfers Against Sewage, which campaigns on water pollution issues) or specific campaigns (for example, Third Battle of Newbury, the campaign against the Newbury bypass), and they have a membership only in the loosest possible sense. These two trends suggest that, even if the membership of the established green pressure groups has made little progress, the total number of green activists and the total amount of campaigning activity may have increased quite substantially.

Drawing conclusions

I think we can draw a number of conclusions from this rag-bag of attitude research:

- Most people agree that protecting the environment is important.

- Most people are ambivalent about the steps they would take.

- Most people are willing to consider sacrificing economic growth for environmental protection.

- There is a vicious circle relating public opinion, media interest, and political commitment.

- Public opinion peaked in 1989 and has barely increased since then.

- People have a poor understanding of environmental issues.

- People don't make the connections between causes and effects.

- There is an urgent need for comprehensive attitude measurement.

Let's consider these in turn:

1. Most people agree that protecting the environment is important

This much is almost trivially self-evident, because the question is sufficiently loaded to preclude "no" answers. The real questions are: How much do people care, compared to how much they care about other pressing issues? How robust is their concern as those other issues become more pressing? And perhaps most important—and least tangible—of all: are they prepared to translate their concern into effective action? For example, in 1995, 90 per cent of people questioned in the British Social Attitudes survey believed traffic congestion would either definitely or probably be one of the most serious problems during the next 20 years [5]; nevertheless, car ownership increased twenty times in the forty years to 1992 [2] and shows no sign of declining.

It's much less clear how people rate the relative importance of environmental issues; it might be interesting to attempt a correlation between such measures and the degree of media coverage received by particular issues over a period of time. We might reasonably expect people to rate as important those issues that they feel affect them most: people who take seaside holidays in Britain presumably rate the problem of sewage on beaches more highly than acid rain (but why, then, is Surfers Against Sewage not the biggest and most influential environmental group in Britain?). The high concern about nuclear waste in Britain in 1986 presumably related to the Chernobyl explosion, and a generalized fear of anything containing the word "nuclear"; that teaches us how confusing people may find the science behind environmental issues.

2. Most people are ambivalent about the steps they would take

Ambivalence. The word that creeps cropping up in discussions of attitudes to the environment. Even politicians claim to stumble on our mass hesitation and confusion. For example, former Secretary of State for the Environment, John Gummer, explains:

"I am in the business of achieving things, of actually winning practical solutions in rather difficult circumstances, difficult because people don't want to think that far ahead". He cites the 'utter ambivalence' of drivers, who want air quality improved without any restraint on their motoring. He explains that many people think his [no smog] strategy is too radical and a burden on the economy. [9]

One thing we do need to determine is whether people are ambivalent as individuals, or collectively in surveys. Quite probably there is a mixture of both. Take the question of spending money to frustrate climate change. An ordinary member of the public might find it difficult to make a clear mental "cost-benefit analysis" when their newspaper has always suggested in the past that global warming is unconvincing pseudo-science. If their paper includes a plausible "pro" quote from Greenpeace stressing the need for action, and a plausible "anti" quote from a respectable industrialist pointing out that this might cost jobs, how can they be anything but ambivalent? Ambivalence could be indecision, but it could also reflect a collective split between people who think very firmly one way and people who think very firmly another, or a split between people with radically different value systems (materialists and the so-called "post-materialists" born after the 1960s, say).

When people are confronted with the responsibility of paying out of their own pocket for tackling environmental problems, ambivalence reappears. Lunch and Rothman (1995) report positive trends in American attitudes to the environment: more people favor the idea that "environmental protection has not gone far enough", that "environmental standards cannot be too high, no matter what the cost", and that "too little is being spent on the environment". Nevertheless, a Gallup survey in 1989 asked if people would be willing to pay $200 in higher taxes to tackle air pollution, and 71 per cent said they would not. Lunch and Rothman conclude:

"... while environmental protection has achieved wide symbolic appeal, there is a difference between announced attitudes and action... careful review of public opinion data reveals that Americans are not willing to sacrifice all other values in order to realize an ambitious environmental agenda" [8].

Green activists and pressure groups show a strange response to this fundamental ambivalence: instead of trying to tackle it head on, they either carry on defiantly, shouting their message even louder and bemoaning widespread apathy, or they assume it doesn't exist at all and that one day, when conditions are right, the environmental cause will magically win everyone over. They concentrate on scientific evaluation of environmental problems, rather than on the public perception of those problems. Friends of the Earth's Charles Secrett:

"Science tells us that we've got some 25 years to implement the solutions, before life becomes a grim struggle for survival.... It won't be easy, but it's certainly achievable. Government knows what needs to be done. People have the skills and technical capacity There is quite enough money. What's missing is sufficient political will and public insistence to change course.... Friends of the Earth and colleague environment and development groups help people fill the vacuum created by selfish ideology, broken political promises and sterile apathy." [10]

But green groups like FoE will continue to make only limited headway with "public insistence to change course", and the political promises that follow behind, as long as they continue to misinterpret perfectly understandable, well-founded ambivalence and confusion as "sterile apathy".

3. People are willing to consider sacrificing economic growth for environmental protection

Some people believe economic growth and environmental protection are quite compatible. This might reflect confusion or ambivalence, but it might also represent fundamental confidence in the status quo. Environment Secretary John Gummer argues:

"The only force which is powerful enough to provide the mechanisms by which we can solve these (environmental) problems is capitalism. What you need to do is to use the government levers of taxation, advantage (subsidy) and, as a last but still a very important resort, regulation, to make sure capitalism works wholly that way. I do find [dirigiste restraints on consumption] an unacceptable view of life, the sort of view that once closed theatres, stopped people having parties, wittered on about the evils of drink." [9]

Misinterpret this as the dogma of a Conservative Party politician, rather than the insight of a perceptive environmentalist, risks obscuring an important message, as a leader in the Independent commented in 1997:

"Priorities need to be set, and a free market is one of the best ways of reconciling competing concerns, but too many green fundis confuse capitalism with markets and are suspicious of attempts to put a price on environmental damage." [11]

David Nicholson-Lord hints that anything more than the most superficial from of environmentalism ("shallow ecology") may have problems with this view:

"If you identify powerfully with nature—if you see pure waters, clean air, a rich and varied biosphere as one of the main reasons for being alive—you're going to want some big changes in urban, industrial society". [3]

In the end, the inability to choose between the old way and the new may simply come down to an almost childish indecision, a more general human failing of the kind described by German writer Elias Canetti:

"Asked which it would rather have, an apple or a pear, a child will either not answer, or will say 'pear', simply because that was the last word that it heard. A real decision, one which would involve separating apple from pear, is too hard for it, for at heart it wants both." [13]

4. There is a vicious circle relating public opinion, media interest, and political commitment

We can only speculate about why public enthusiasm for green thinking peaked in 1989. Most likely, it was like a kind of planetary alignment, a conjunction of favorable circumstances. As David Nicholson-Lord points out:

"1988 had already proved itself a powerful recruiting sergeant for environmental groups... In the North Sea, a mystery virus linked with pollution killed thousands of seals. Toxic wasteships wandered the coasts of Europe seeking a port of entry. In the US, climatologists warned that global warming had arrived, and storm, drought and heatwave across the continents seemed to confirm it" [9].

Later that year, Margaret Thatcher described the environment as "one of the great challenges of the late twentieth century". It seemed environmental politics had found its thermal, a vicious spiral to dizzy new heights of action and concern.

As Robert Garner points out, there is a correlation between public opinion and media coverage—something that comes as no surprise [7]. It is clear that political commitment takes considerable notice of strong public opinion, and that media coverage will pick up on apparent changes in policy. The challenge for green activists and pressure groups, then, is to apply pressure at some or all points of this spiral.

5. Public opinion peaked in 1989 and has barely increased since then

So why has progress since 1989

been so slow? It's easy to write this off simply to the mid 1980s

economic

recession, even if there is a tendency to reassert the importance of

economic growth when the economy performs poorly, incomes are

suffering, and people are unemployed. But other factors are important

too. To borrow a marketing term, the market for green concern might

simply have reached saturation—it's perfectly possible that the more

vocal green groups like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth have

reached as many active supporters as they're ever going to, without

broadening the market, and appealing to different types of people. This

might be explained if the wider population is indeed becoming

habituated or sensitized to messages of eco-doom and global

catastrophe, or if people are genuinely confused and can't find a

meaningful way to participate, or if there is an insurmountable wall

between superficial green concern and a deeper viewpoint. These and

other reasons for popular ambivalence are considered in the next

section.

In terms of the spiral theory, it's clear that faltering public opinion has allowed politicians to go soft on environmental commitments, and given them an excuse not to back up their rhetoric. As Hugo Young points out: "Establishment politics... have a tendency to retreat from the multiple inconveniences of environmental issues unless the practitioners are kicked hard and often." [12] If the public and the politicians start to lose interest, so do the media... leaving only the green groups to keep concerns ticking over, but making relatively little decisive progress.

But, as environmental journalist Polly Ghazi suggests, although media coverage of the issues has subsided, it has also matured:

"Ecology may not dominate the front pages in the way politics, the economy or Europe does. But pick up any broadsheet newspaper, middle-market tabloid or mass circulation magazine and the environmental dimension now pervades the features, health, science, business and even motoring pages to a degree unthinkable five years ago." [24]

The 15 per cent Green Party haul in the 1989 European elections may simply have been a fluke. Indeed, Stuart Brown argues against drawing simple conclusions from the progress of other European Green parties:

"The progress of Green parties is not by itself an accurate barometer of increasing concern about environmental issues. In the Netherlands, for instance, it has been claimed that the reason why there was no Green party is that the main political parties put a considerable emphasis on environmental questions, in response to public pressure. The relative success of Die Grünen [the German Green Party] has been partly due to its strong commitment to nuclear disarmament at a time when the major political parties supported the retention of NATO nuclear bases on German soil". [19]

Acid rain, which has devastated up to 75 per cent of some parts of the Black Forest, may also be a significant factor, for as Elias Canetti points out, the forest is a central part of the German psyche:

"The crowd symbol of the Germans was the army. But the army was more than just the army; it was the marching forest. In no other modern country has the forest-feeling remained alive as it has in Germany. The parallel rigidity of the upright trees and their density and number fill the heart of the German with the deep and mysterious delight. To this day he loves to go deep into the forest where his forefathers lived; he feels at one with the trees." [13]

6. People have a poor understanding of environmental issues

Several surveys have confirmed that one of the main problems with public attitudes to the environment is a basic confusion about the science involved. In 1991, a survey by the DoE found poor understanding of many issues. Asked to name the main problem behind climate change, 25 per cent of people wrongly picked the hole in the ozone layer [4]. In a more recent survey in 1993, 42 per cent of people got the question right, but this time 38 per cent wrongly picked the hole in the ozone layer [6]. In the early 1990s, the Department of the Environment produced a leaflet called "Wake up" designed to explain environmental issues and concerns. A study conducted by MORI in 1981 to measure the effectiveness of that leaflet found 90 per cent of people claimed to be interested in the environment, 80 per cent wanted to know more, and 50 per cent did not fully understand the issues [4].

Campaigning environmentalists usually come from a scientific or technical background—usually a positive disadvantage when it comes to explaining things clearly to non-scientific members of the public. Why should ordinary people be expected to understand, with no help, the mechanism of global warming, what red tides are and how they occur, whether there is any real danger from eating genetically modified foodstuffs, or how CFCs break down the ozone layer? As William H. Baarschers points out, campaigners can exaggerate the scientific doubts for their own benefit, undermining the honesty and integrity that are the backbone of activism, and undermining their own purpose in the long run. Greenpeace has repeatedly faced this criticism, most recently over its campaign to disrupt GMO test sites:

"If Greenpeace had been interested in scientific debate, it would have allowed this perfectly legal experiment to go ahead. GM crops have so far harmed nobody; neither is there any clear proof of environmental damage. Greenpeace, though, is in the business of whipping up mass hysteria against multinational corporations, as it successfully did in the Brent Spar case. In such a febrile atmosphere, no rational debate is possible." [28].

Baarschers points out just how easily science can be abused:

"We must once more underline the very important distinction between the scientific fact and the opinion of the scientist. In the case of opinion, it is imperative that we inquire if we deal with a scientific opinion, based on expertise, or with the opinion of a person who just happens to be a scientist." [18]

But the often pretend objectivity of science also frustrates healthy reactions of sadness and fury where environmental threats are concerned. Science gets in the way of emotion, and who is to say which is most appropriate? "Habitat", "ecosystem", "Site of Special Scientific Interest"—none of these conveys the heart-stopping flash as a kingfisher dashes past you for the first time. Richard Mabey argues:

"When we come down to a favorite old pollard willow, blown over in a stream, colonized for a few years by an improbable collection of birds and plants, and finally washed away, it would be an affront to its character to try to assess it purely in scientific terms, and absurd to think of it as a 'site'. Its short-lived fascination could only be secured inside a set of principles for managing the wider countryside which has room to consider the small place and the personal meaning." [23]

Witherspoon uses attitude research to argue that people with less scientific knowledge are more likely to take a "romantic" view of nature and have an environmentally gloomy outlook:

"There are clear romantic, quasi-religious overtones to some aspects of public attitudes towards the environment. That is, some people's concern seems to stem primarily from a gloomy assessment of the role of science and human intervention in a romantically conceived state of pure and uncorrupted nature. Those who espouse this sort of romantic environmentalism are particularly unlikely to have a very clear sense of which policies might best address their concerns." [26]

Deep ecologists, such as Devall and Sessions, would see this as a naïve assessment:

"Environmentalism is frequently seen as the attempt to work only within the confines of conventional political processes. However, this approach has certain costs. Reformist activists often feel trapped in the very political system they criticize. If they don't use the language of resource economists—language which converts ecology into 'input-output models,' forests into 'commodity production systems,' and which uses the metaphor of human economy in referring to Nature—then they are labeled as sentimental, irrational, or unrealistic." [29]

7. People don't make the connections between causes and effects

It follows necessarily that, if people don't properly understand environmental problems and their causes, they will not be able to form a wider green consciousness. Environmental awareness will catch them like baby fish and throw them back in the river; and they will need to be "hooked and reeled in" time and time again as successive environmental issues go through cycles of importance. As The Independent commented:

"Does the energy used in recycling do more damage than the depletion of finite resources in making new things? Is there any point in saving energy while the world's population grows so fast? But the truth is that these questions are linked." [11]

Without a wider green understanding of environmental issues, their causes and effects, and the links between them, people will remain ambivalent to green propaganda, and susceptible to "green backlash" from organizations and ideologies who oppose the green agenda.

8. There is an urgent need for comprehensive attitude measurement

More than anything else, what emerges from this brief review of attitudes and opinions to the environment is that we need more systematic research. It may suit governments and political parties not to know the strength of feeling about the environment, but it would certainly suit NGOs and campaigning organizations to know who their existing supporters are and where their new ones might come from. Money spent on decent, reliable attitude measurement would be just as valuable as scientific studies of climate change, ozone depletion, and the rest.

Why are people ambivalent about the environment?

It's vital that we understand the gap between public concern and public or political commitment, both on the environment and on other issues. The American political activist Noam Chomsky offers an example concerning military spending that illustrates the problem well:

"Under Bush and Clinton, the US had taken over of the arms market for Third World countries—85 per cent of the arms going to 'nondemocratic governments' as defined by the State Department, a policy that is opposed by 96 per cent of the population." [14]

When 96 per cent of Americans oppose the sales of arms to oppressive regimes, how does the US government get away with this?

There are plenty of similar—if less spectacular—examples in the research on attitudes to the environment that we have already considered. But to take a fresh example, in 1995, 89 per cent of people agreed that traffic congestion will be one of the most serious problems in Britain within the next twenty years [5]. Nevertheless, in 1996, the then Conservative government reasserted its commitment to a '6 billion trunk road program [15]—a policy of building even more roads to generate even more traffic, rather than attempting to tackle the fundamental causes of traffic growth [16]. There are as many examples as we care to look for.

If there's to be any hope of saving the environment, green activists must focus on closing this gap, ensuring that political commitments accurately reflect—rather than gloss over—public concerns. They also need to consider how ordinary people can be ambivalent about major environmental concerns that, to them, seem overwhelmingly persuasive.

Most people don't really have a clear idea of how they feel about specific environmental issues. As Elias Canetti suggests: "Often we do not know what we think until a question is put to us. As long as it is polite it leaves us free to decide for or against, but it forces us to come down on one side or the other." [13] So part of the ambivalence shown up by the research quoted here may be a simple reflection of the fact that people are making their minds up on the spot, responding to single questions from interviewers, rather than carefully balanced arguments. Polling is artificial—a macro-scale example of Heisenberg's "uncertainty principle": the very act of measuring something interferes with the measurement. This is another reason to conduct more attitude research involving detailed interviews with a few individuals, focus group sessions, and so on.

But there are many other reasons for conflicting attitudes. One of the most obvious reflects the powerful self-interest of the status quo. Why should highly profitable water companies stop polluting beaches when they know government agencies are a soft touch, and cleaning up their act would be expensive? Why should newspapers point fingers at their car company advertisers over pedestrian traffic casualties or childhood asthma? Why should the problem want to turn into a solution when it's perfectly happy as it is?

The "problem" may go further, systematically obstructing any attempts at reform or confusing those investigations that seek to uncover the truth. In an impressive investigation, Andrew Rowell has carefully documented the phenomenon of "green backlash" orchestrated attempts by business and extreme right-wing interests in the United States and Britain to undermine the green movement [17]. Environmentalists find themselves the victim of nasty counter-PR; all of a sudden, they are "eco-fascists" and "eco-terrorists", out to destroy rather than protect. Backlash is not needed where "greenwash" will do—a fake slap of environmentally-friendliness. Corporate PR firms make a specialty out of glossing over occasional environmental "hiccups" such as the Union Carbide chemical explosion in Bhopal, or more systematic eco-plunder, such as logging in Malaysia or human rights abuses in Indonesia. The greens argue one way, the PR men argue the other, and the public are caught in the conflict of crossfire, not sure who's telling the truth, or who to believe. No wonder they're ambivalent.

What are ordinary people supposed to think? As Baarschers argues, middle-ground public opinion is turned off--not won over--by polarized argument:

"The monkey on our back in the industrialized world is the combination of our lifestyle and its associated overconsumption, with the vast number of our species. The 'coercive utopians' would have us go back to a simpler lifestyle. The catastrophists believe that, since nature knows best, an environmental calamity will turn the clock back for us. So far they have all been wrong. And the cornucopians maintain that science and technology will solve all problems. So far they have not been right. What are pragmatists to do?" [18]

Not knowing who to believe is only one problem, however. Sometimes there just seem to be just too many problems to cope with. Just as we're trying to understand here why people don't show more inclination to fight environmental problems, so we might question their indifference to the global refugee crisis, child exploitation in India, human rights abuses in East Timor, or the drugs trade in Colombia; or in this country, inner city degradation, crime, homelessness, care and dignity of the elderly, or a dozen others. John Gummer warns of the dangers of not getting bogged down in the immensity of the task:

"There is a balance to be achieved about warning people of the dangers, explaining how much has to be done, on the one hand, and giving people confidence that it can be achieved on the other. If you want people to do enough to combat man-made climate change it's no good saying it's so big, so huge, so enormous a problem that you have to make cataclysmic changes in your lifestyle—because if you do that you know they'll say no." [9]

Taken to its logical conclusion, ethical consumerism (selecting products according to the ethical practices of their manufacturers or retailers) could become a matter of living off air and water. Meat is murder. Cosmetics are tested on beagles. Banks fund the arms trade. Burger companies are behind deforestation. How far are we willing to take this? Not very far, if Witherspoon is correct and only one per cent of people are absolutely ethical consumers [26].

Gummer, again, warns that environmentalists may be guilty of "selling the environment wrongly":

"We've tended to talk about it in sort of puritanical terms, as if we would all be that much better off if we were all a bit slimmer and did that much more exercise and ate rather less... which gives the environmentalists the open-toed sandal kind of image. You must not sell it on the syrup of figs theory that the nastier it tastes the better it does you." [9]

Certainly, the greens have often made saving the environment seem hard work in the past.

They wear their greenery like a fig-leaf, making no apologies for its obvious inadequacies. Going green is hard work, but they never tell you that. "Come on in, the water's horrible!" they seem to grimace, wondering why so few of us follow them. One of the definitive guides to becoming green, written by John Button for Friends of the Earth, offers a couple of hundred variations on the basic hair suit:

- Use your car as little as possible.

- Set central heating thermostats relatively low and only turn them up if it is uncomfortable.

- Look at the household machinery you have and ask yourself whether you really need it all. Sell or give away what you don't need.

- Avoid detergents as much as you can.

- Think carefully about buying [furniture] second-hand, especially for basics like tables, chairs, and bedsteads.

- Make a point of discussing programs afterwards, especially with children

- If you do get a dog, get a small one rather than a large one.

- Try to avoid tins and packets: they are less healthy than fresh food and you pay for the packaging.

- Find out about yoga classes in your area [21].

All of this makes perfect sense to committed environmentalists, but is particularly unappealing—indeed, quite appalling—to ordinary members of the public. Going green is hard work—but can't ordinary people be helped in more gently, if the alternative is that they turn their backs and walk away? Don't people have enough excuses for doing nothing as it is?

Depending on where you stand, as Jonathan Raban suggests, a green lifestyle seems either upright worthy or downright absurd:

"It is a wonderfully cozy way of avoiding the abyss. When ecology entered the language as a popular epigram, it was easily converted into a series of simple injunctions: we were to go back to the country, live with bicycles and mangles, eat vegetarian food, and stoke log fires under the leaky thatch." [22]

John Gummer agrees. The way to convert people is by gentle encouragement, praising real achievements: "You don't get the best out of people, you don't stretch them that much further, unless you are constantly making them aware of your recognition of what they have done." [9]

This squares with Labour politician Ann Taylor's view, that the key to change is involving ordinary people and communities, giving them a stake in making change possible, empowering them, and rewarding them with the satisfaction of making a genuine contribution to improving our common future [25].

Where is public opinion heading?

To sum up, then, nothing characterizes public attitudes to the environment better than this one word: ambivalence. There's a canyon between public concern about environmental problems and public commitment to doing something about them.

As Sharon Witherspoon concludes from a detailed review of attitude surveys, widespread environmental concern is reflected neither in support for hard-hitting environmental policies, nor in environmental activism: "Our research suggests that much of the British public's concern about the environment is (still) relatively superficial." She demonstrates that any account of environmentalism as "simple post-materialism" is naïve, suggesting some distinctly different environmental agendas. She contrasts "romantic" views of the environment (quasi-religious, suspicious of science and technology, celebrating uncorrupted nature, gloomy about the environmental future) with "rational" views (scientific knowledge, anti-materalist stance, classic liberalism, less pessimistic about the future, more tendency to political activism). And she concludes:

"Governments interested in increasing public support for the hard environmental choices which lie ahead may need to do more than increase public awareness of how the environment works. They could, of course, attempt to increase environmental pessimism as a way of increasing willingness to bear the costs of green policies, but that is likely to make for a shriller public debate. Rooting the debate about the environment in a discourse centered in concern for others, and on a sense of collective identity, may be a more stable route to a 'green' Britain. That this too is a form of romanticism may be less important if it works." [26]

This is an intriguing analysis. Starting off from a position that appears to disparage the "romantic" view with its "quasi-religious overtones" ("those who espouse [it]... are particularly unlikely to have a very clear sense of which policies or actions might best address their concerns"), Witherspoon nevertheless seems to conclude that rational policy arguments alone will not be up to the job. Ultimately, she suggests that green ideas will find most favor in socially- or collective-minded governments, and that a deeper change in values is required.

This is not so far from the arguments of "deep ecology"—that the real reason for the greens' relatively modest inroads is that they are still attempting to treat the symptoms, rather than the disease, tackling effects, not causes, and that this might be addressed by adopting a different set of values. As Arne Naess argues:

"Ecologically responsible policies are concerned only in part with pollution and resource depletion. There are deeper concerns which touch upon principles of diversity, complexity, autonomy, decentralization, egalitarianism, and classlessness.The emergence of ecologists from their former relative obscurity masks a turning point in our scientific communities. But their message is twisted and misused. A shallow, but presently rather powerful movement, and a deep, but less influential movement, compete for our attention." [20]

In other words, if real change is the goal, rather than superficial concessions to the nuisance of protest, greens should be arguing from a more considered position of integrity and responsibility for a wholesale shake-up of values. This is the essence of deep ecology, "living as though nature mattered"; asking fundamental questions and maybe starting again from a new set of attitudes based on modesty, tolerance, diversity, and so on. The question then becomes how best to engage other people in what is tantamount to a pragmatic religion based on a deep respect for all the things that are good and successful about nature. With the distinctly un-notable exception of Consumerism, most religions these days are little more than ghetto cults—something environmentalism can least afford to remain. But is there any prospect of a mass migration to "deep ecology" any time in the near future? And if not, what is the alternative?

Witherspoon

argues that public

awareness and understanding will not sweeten the environmental

medicine: tougher regulation and higher taxes. But it might be a matter

of simply finding a Trojan horse—a matter of compromise, less about

common ends than common means; whatever the common ground might be,

let's seize it and start from there. Low-energy lightbulbs are indeed

good for the environment, but they're also good for your pocket.

Cycling or walking instead of taking the car is a lot cheaper, and

probably more fun, than quack diets and exercise videos. Getting a job

nearer home saves oil for better things, but it also gives you more

time with your family and makes your local community more than just a

dormitory. Giving up the daily commute and switching to homeworking is

better for the planet, but it means you can live further out of London.

Similarly, as Polly Ghazi suggests, being green makes economic and

political sense: "Many green pledges, such as setting up a national

environmental accounting system to run alongside GDP, are cost-free,

while others, such as investing in green technology, will create new

jobs" [25]. Perhaps this, then, is the true object of environmentalism:

not

to make itself a mass movement, but to trickle environmental

consciousness quietly, almost unnoticed,

into every aspect of all our lives?

Ten years on

This article was written mostly in 1997 using surveys and sources (mainly British) from the mid-1990s and before. In 2007, the British government's environment ministry (Defra) published new attitude data in its 2007 survey of public attitudes and behaviors toward the environment (archived web page via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine). At the time of writing, the latest data on British attitudes is in Defra's 2011 Survey of public attitudes and behaviors towards the environment (archived web page via the UK National Archives). You can now also download the datasets from that survey.

References

- "Beware: 56-year traffic jam ahead", Daily Mail, 1997.

- "Transport trends and transport policies: Myths and Facts", Transport 2000, London.

- "Waves of Concern", David Nicholson-Lord, Earth Matters, 33, Spring 1997, Friends of the Earth, London.

- The UK Environment. London: HMSO, 1992.

- Social Trends 27. London: The Stationery Office1997.

- Social Trends 26, London: HMSO, 1996.

- Garner, R. Environmental Politics. Prentice Hall, Hemel Hempstead: 1996.

- Lunch, W. and Rothman, S. "American Public Opinion: Environment and Energy", in Simon, J. (ed) The State of Humanity. Oxford: Blackwell,1995.

- "True Blue: Deep Green", an interview with John Gummer, Nicholas Schoon, Earth Matters, 32, Winter 1996, Friends of the Earth, London.

- Editorial, Earth Matters, 30, Summer 1996, Friends of the Earth, London.

- "Saving the world needs leadership not arson", The Independent, 13 January 1997.

- "Swampy & co have a lesson for the Greens", Hugo Young, The Guardian, 13 March 1997.

- Canetti, E. Crowds and Power. London: Victor Gollancz, 1962.

- Chomsky, N. Powers and Prospects: Reflections on Human Nature and the Social Orde. London: Pluto Press, 1996.

- Government Commitment to '6 billion trunk roads programme. Department of Transport Press Notice 357, 26th November 1996.

- Trunk Roads and the Generation of Traffic. Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment (SACTRA). London: HMSO, 1994.

- Rowell, A. Green Backlash. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Baarschers, W. Eco Facts and Eco Fiction. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Brown, S. (1990). "Humans and the environment: changing attitudes", in Environment and Society, The Open University, UK.

- Naess, A. (1973). "The Shallow and the Deep, Long-range ecology movement. A survey.", Inquiry, 16.

- Button, J. How to be Green: the Friends of the Earth Guide. London: Century Hutchinson, 1994.

- Raban, J. Soft City. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1974.

- Mabey, R. The Common Ground: A place for nature in Britain's future?, London: Hutchinson, 1980.

- "Do the media conspire against the environment?", Polly Ghazi, Earth Matters, 33, Friends of the Earth, London, Spring 1997.

- Taylor, A. Choosing our future: a practical politics of the environment. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Witherspoon, S. (1994). "The greening of Britain: romance and rationality", in British Social Attitudes, 11, Social and Community Research, Dartmouth, London.

- "What on earth has this lot achieved?", Jonathon Porritt, The Daily Telegraph, 16 November 1996.

- "Greenwar", Editorial leader, The Daily Telegraph, 28 July 1999.

- Devall, B. and G. Sessions. Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered. Salt Lake City, Utah: Gibbs Smith, 1985.

Find out more

Books

- A New Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations by Clive Ponting. Penguin, 2011. A general history of environmentalism and the ideas behind it.

- Break Through: Why We Can't Leave Saving the Planet to Environmentalists by Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. A "third way" argument between the polarized positions of hard-line environmentalists and their economic critics.

- The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State of the World by Bjørn Lomborg. Cambridge University Press, 2001. An economic rebuttal of environmental arguments (itself greeted with great skepticism by environmentalists).